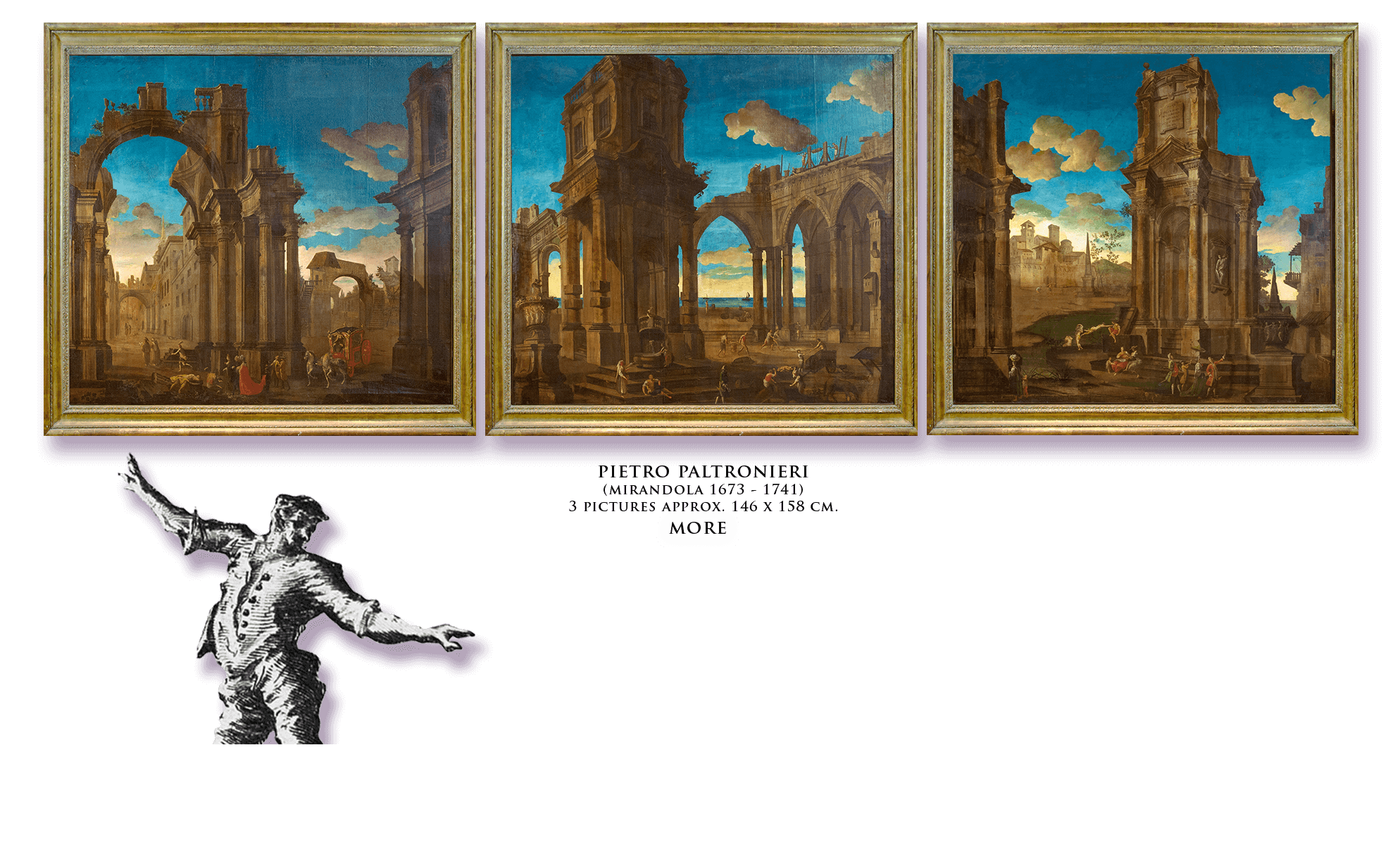

17th and 18th Century Italian Ruin Paintings

Picturing the Past and Its Remains

Figure 1. Gian Paolo Panini, Figures Conversing Among the Ruins, oil on canvas, ca. 1760.

One oddly balmy London evening, several years ago, we shared dinner with the head of Old Master Paintings of a pre-eminent auction house. The up-to-the minute fare was nicely-lubricated (dry French whites), and in time our learned, sharp-eyed, sociable companion came to hold forth on the large issues. “The history of Art,” he confided, in a soft voice, approaching a whisper, “is a history of names.” Especially, he suggested, the history of big names – important artists. Think less of great periods and places, influences and rivalries, society and politics. Think more about genius. There’s little quarreling with this apparently simple truth, a truth that has so well served the progress of Art commerce and culture since the Renaissance.

The history of Italian architectural paintings, though replete with difficult geniuses of every stripe (‘names’ galore) is a tale somewhat more complex – a truth positioning this genre of Art in the quieter corners of the phenomenon of Old Master paintings. It’s an out-of-the-way precinct for an Art movement without which, according to Rudolf Wittkower, among the great ‘names’ of Art History, French Impressionism would have arrived stillborn.

Before outlining the history of Italian architectural painting, we’d like to say more of what it is and why it rivets our attention. The subjects of this genre, which arose in the first part of the 17th century and persisted until the last part of the 18th, are remarkably similar from artist to artist, canvas to canvas. Almost always, these paintings focus upon antique Roman architectural ruins. Almost always, these pictures (Art historians describe them with the Italian – capriccio) are of two types – realistic views of ancient landmarks (called vedute essate, or vedute reale) and of imaginary ruins (called vedute ideate). Roman painter Gian Paolo Panini (1691 – 1765), the foremost name with this genre of painting – “the one master who raised vedute of all types to the level of great art,” writes Wittkower – invented a hybrid approach (fig. 1), picturing real ruins in imaginary juxtapositions with each other, commingled with architectural elements of his own devising.

Figure 2. Monogrammist GAE, Alexander at the Tomb of Achilles, oil on canvas, perhaps ca. 1640.

While the central visual subjects of all these pictures are the colossal, hulking, ancient ruins of Roman civilization, both real and fanciful, these places are also always inhabited – by common folk, by aristocrats, by History’s great personages (fig. 2), by thieves and other scoundrels, occasionally by painters. What all these people share, of course, is their tiny (nearing insignificant) stature, next to the monumentally-scaled, overgrown and decrepit remains of the spectacular past.

These pictures, it seems to us, may be “read” along a line – the pathos of our reduced present amplified by the past’s splendor at one end, humanity’s remarkable tenacity, surviving the great traumas which’ve brought low magnificent empire, on the other end – a line, then, running roughly from despair to hope.

For us today, the question is of our place along this line and the jury is still out. Vulnerabilities to cataclysm, of one kind or another, underline the ways in which our lives now are not very different from those illustrated in these paintings, beginning 400 years ago – not very different from those tiny people making their way amongst the ruins. Large forces, set free, are now at work; the path and plan of civilization hardly clear.

Before wandering further into these murky matters though, let’s return to the relative clarities of the history of Italian architectural paintings.

Over the past 2500 years of Western Art, Architecture has often provided the frame, the setting for painting, from certain Greek vases to early Renaissance views of cities, from late Renaissance paintings of Dutch interiors to Pop Art pictures of American living rooms. In each of these instances, Architecture forms a figurative place, a kind of stage on which the action of the picture proceeds. This, of course, is what we expect of real (as opposed to pictorial) architecture – buildings harboring human life.

Figure 3. Andrea Pozzo, detail, The Apotheosis of St. Ignatius, St. Ignatius Church, Rome, fresco, 1691 – 1694.

Very much more unusual in Western Art history are paintings whose subject is Architecture itself. Among the earliest of these are certain Pompeian and other Roman wall murals, dating to the first century B.C.

The subject was taken up again in the Renaissance, in a big way, by two big ‘names’ – Andrea Mantegna (1431 – 1506) and later, Antonio da Correggio (1489 – 1534). Both undertook the creation of illusionistic architectural space, employing the latest understandings and advances in perspective. Their paintings, applied at a large scale, appeared to extend the interiors of places in scenographic, highly dramatic, even miraculous ways and were, in their time, sensations.

As well, they set the stage for the full flowering of architectural pictures in the Italian Baroque, beginning in the first part of the 17th century, with the designs of two more “names” – Giovanni Lanfranco (1582 – 1647) and Pietro da Cortona (1596 – 1669). Both continued the architectural directions of their Renaissance predecessors at large scale and in fresh directions.

The apotheosis of this sort of highly refined, expressive, and swirlingly overwrought trompel’oeil architectural painting, called quadratura, is reached in the work of, yes, another “name” – Andrea Pozzo (1642 – 1709). While earlier pictures by his predecessors appear to us now as skilled, engaging, if slightly academic, undertakings in perspective and foreshortening, Pozzo, three hundred years later, leaves us gasping for breath, with the sheer magnificence of his virtual place-making! (fig. 3)

Figure 4. Giovanni Ghisolfi, Philosophers Conversing Among the Ruins, oil on canvas, ca. 1660.

No discussion of quadratura painting is complete, nor can the phenomenon of Italian architectural pictures be understood (nor, for that matter, the etchings of Piranesi and others) without mention of an entire family of ‘names’ – the Galli da Bibiena. Unlike Cortona and Pozzo, who were architects as well as painters, the Bibiena were set and stage designers. Thus, no taint of architectural propriety or necessity infects their lavish painted fantasies, produced across Europe for operas, festivals, weddings, funerals, and state events. By nature temporary, little remains of their decisively influential work, beyond some highly rendered and suggestive drawings.

While the phenomenon of quadratura assists our understanding of the architecture of Italian architectural paintings, other influences, other ‘names,’ other genius is also at work with these pictures’ landscapes and figures.

Roman ruins painters, according to Rudolph Wittkower, were influenced by the serene, pastoral settings created by Jan Frans van Bloeman (1662 – 1749) and Andrea Locatelli (1695 – 1741) – both landscapists (Wittkower describes them as “topographical painters”) who often included ancient ruins in their work.

A pivotal influence, though, here and in much else with Italian Baroque painting, is the Neapolitan Salvator Rosa (1615 – 1673), who overturned this species of placid landscape, replacing it with others tempestuous, subversively replacing aristocratic figures with banditti, (often pictured robbing aristocrats) “….most unorthodox and extravagant,” observes Wittkower, adding that the “Neapolitan landscapists – Greco, Cappelli, Coccorante ….(all artists in Piraneseum’s catalog) stem mainly from Rosa.”

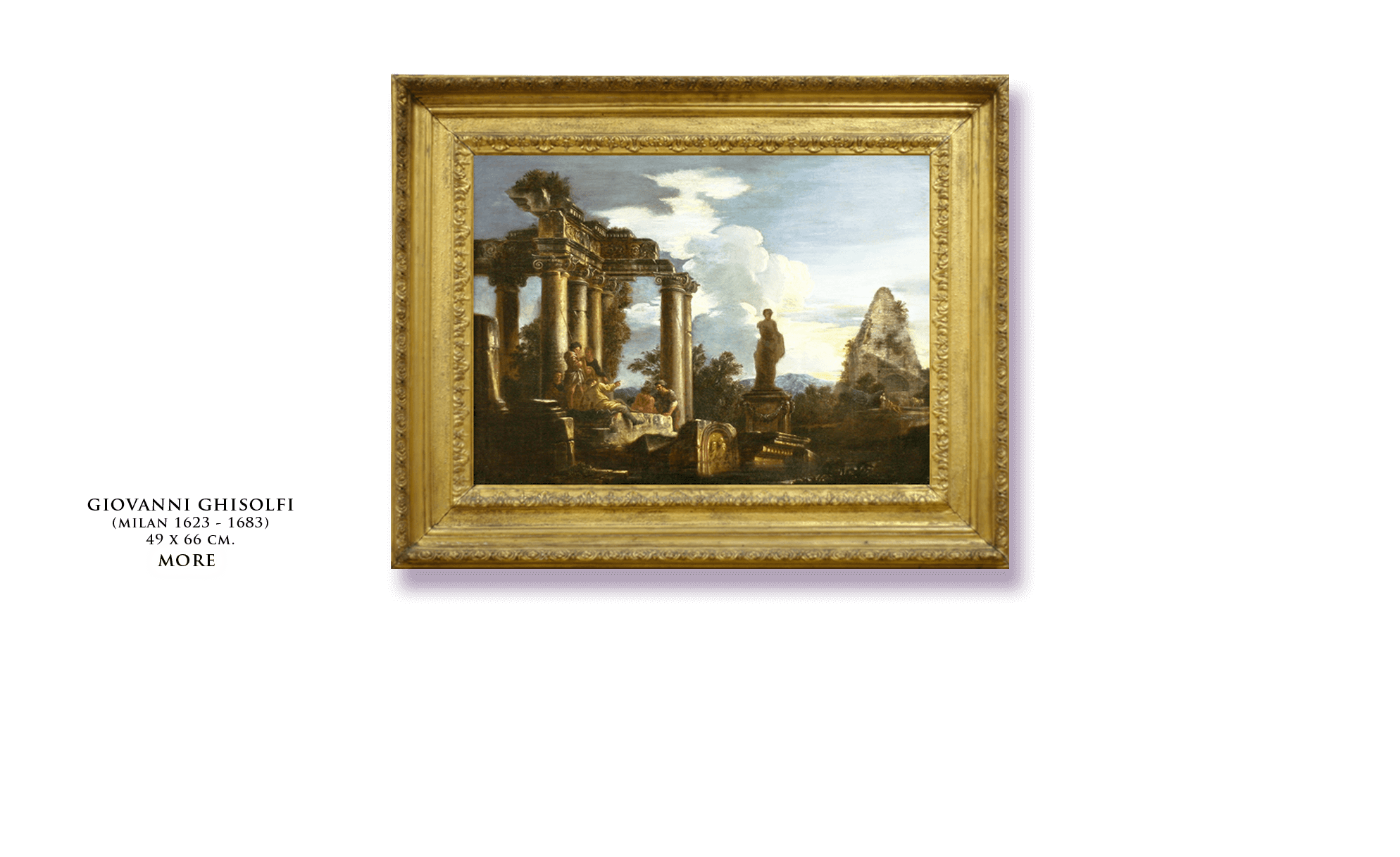

Rosa’s influence reaches northwards as well. In Rome, in the 1670’s, he befriended painter Giovanni Ghisolfi (fig. 4) (Piraneseum’s catalog includes several of his articulate canvases), and occasionally added figures to his friend’s pictures. Here, it shouldn’t be forgotten that Ghisolfi’s example guided the work of the greatest “name” with Italian capricci, 18th century Roman artist Gian Paolo Panini (1691 – 1765).

At least as important an influence on the landscape and figures in Italian capricci as the Neapolitan Rosa, though, was a crowd of largely Dutch and Flemish painters – the Bamboccanti – who came to Rome in the first part of the 17th century. By 1623, the Dutch among them had organized a guild, which Wittkower describes as a center of Bohemianism.

Figure 5. Francesca Guardi, Capriccio With Ruined Arch, oil on canvas, ca. 1770.

Italian ruins painters, highly trained in quadratura and landscape, but less skilled with the human form, often employed the Bamboccanti, who populated their canvases not with the classicizing or historical figures often seen with Ghisolfi, nor with Rosa’s banditti, but with the everyday folk of the 17th century Roman street (though many look as if they’d be more at home in Amsterdam!).

With the Bamboccanti’s own paintings, Bohemian subjects included a genre called ‘tavern scenes,’ rather than the more familiar, more august settings. This approach, reasonable-sounding to us today, was contravertial. Those favoring the official Classicizing approach to Roman paintings were aghast, describing these paintings as ‘unprincipled,’ ‘primitive,’ and employing ‘degraded subjects,’ writes Wittkower. However, history reveals the Bamboccanti, in “employing the field of human experience, (were) fighting the battles of the future.”

That future led, eventually, to 18th century Venetian artists directly influenced by Neapolitan and Roman architectural painters; by landscape artists; and by Rosa and the Bamboccanti, says Wittkower. He further observes that this helped form the roots required for the flowering of that period’s Venetian painting, including the accomplishments of more ‘names’; Marco Ricci (1676 – 1730), Canaletto (1697 – 1768), Bernardo Bellotto (1722 – 1780), and eventually Francesco Guardi (1712 – 1793) (fig. 5), all capriccio painters! And it is, paraphrasing Wittkower, just a hop, skip, and a jump from their shimmering scenes of La Serenissima, painted by this crowd, to the esteemed advances of French Impressionism.

Figure 6. Viviano Codazzi, figures by Michelangelo Cerquozzi, The Colosseum and Arch of Constantine, oil on canvas, ca. 1660.

Of course, Italian capricci are very much more than the sum of their influences – more than a measure of quadratura, plus a dash of da Cortona, and a splash of Rosa, Bamboccanti to taste. The greatest forces in the development of this genre were the painters themselves – their varying talents, training and travels, commissions and artistic alliances, as well as matters less often factored in – personality and temperament, friends and enemies, reputations, good fortunes and (sometimes very) bad luck.

Let’s take up this last first. Among the painters in Piraneseum’s Catalog is a smaller canvas, picturing a ruined temple by a seaport, painted c. 1697 by the Neapolitan Gennaro Greco, also called Il Mascacotta (Italian painters of this period, like certain baseball players today, often carried nicknames). We wondered about the meaning of this name, before puzzling it out as, approximately “he of the cooked face.” Gennaro had suffered disfiguring burns as a child (bad luck). He was, however, a successful painter and married three beautiful women (good luck). In 1714, while painting a ceiling mural, he fell to his death from a high scaffold (bad luck). His fame was sufficient that a chapter of Bernardo da Domenico’s 1742 Vite dei Pittori, Scultori, ed Architetti Neapolitani is titled Gennaro Greco (more good luck), with the most minor mentions of other painters working at the same time, including Leonardo Coccorante, another painter featured in Piraneseum’s Catalog. Forward to the 21st century and “he of the cooked face” has been almost entirely forgotten (very bad luck), largely supplanted by painters who scarcely rated a footnote 275 years ago (insult plus injury!).

Figure 7. Leonardo Coccorante, Capricci with Figures and Ruins by the Sea (pair), oil on canvas.

Another example – not even a 100 years ago, Gian Paolo Panini, whose talent is now considered surpassing, was thought merely derivative of Giovanni Ghisolfi.

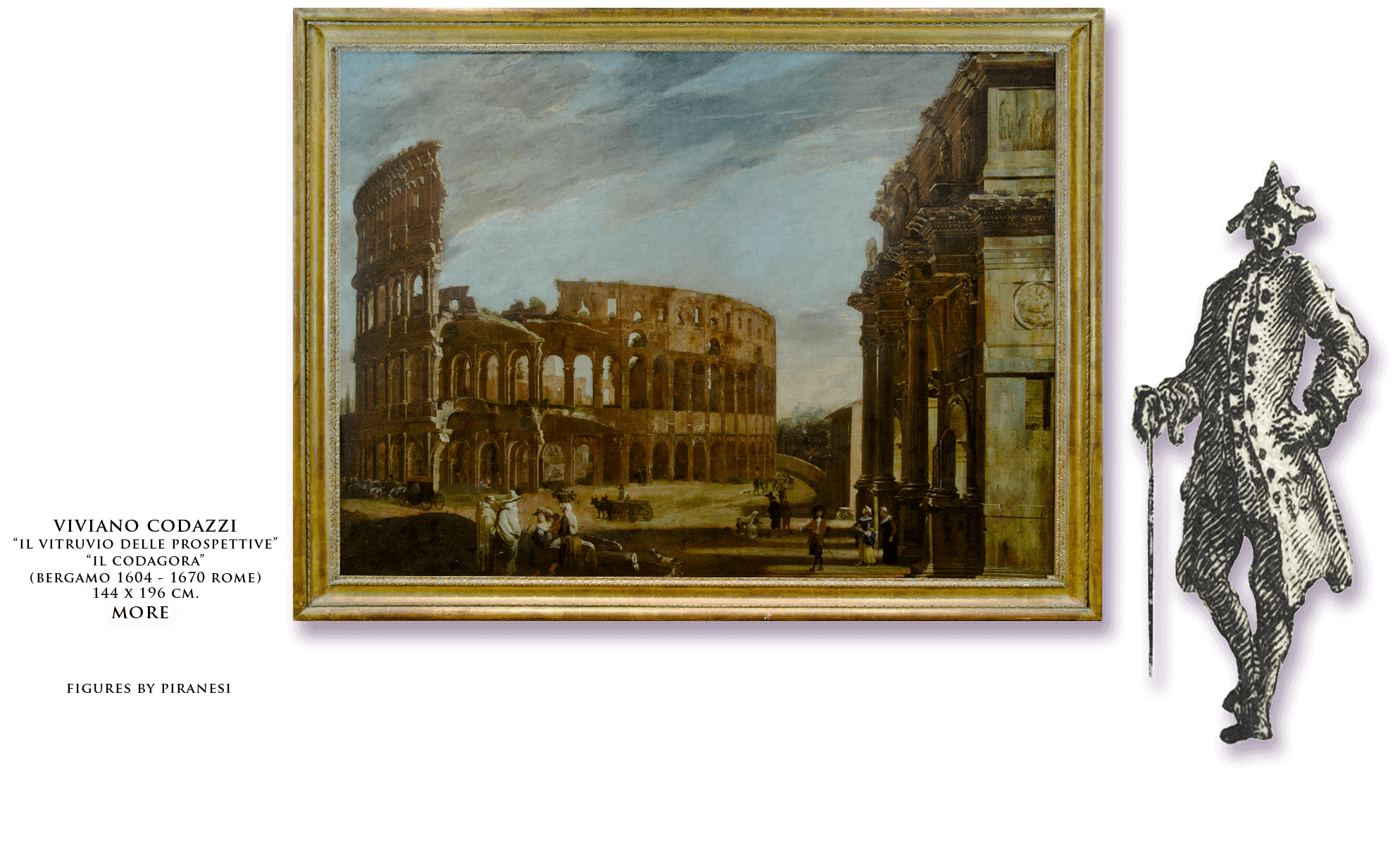

Piraneseum’s Catalog includes a variety of the more formative anecdotes (and juicier gossip) regarding many of the artists central to the phenomenon of Italian capricci. Included are nearly a dozen “names,” ranging from major to minor (as we’ve seen, some have, in the intervening centuries since they worked, been thought both major and minor). They are presented chronologically, beginning with the most important Italian High Baroque architectural painter – Vivianno Codazzi. Offered is a splendid, large and impressive veduta of the Colsseum and Arch of Constantine, dating to the 1650’s (fig. 6).

Working slightly later in the century is Giovanni Ghisolfi, a key figure in the development of the genre of architectural fantasy or capriccio painting. Of course, most artists worked in multiple genres; and this Catalog includes three pictures by Ghisolfi, two capricci of Roman ruins, as well as a realistic view of the Arch of Titus in Rome’s Forum. These paintings exhibit the artist moving to smaller canvases, for Grand Tourists to carry home as souvenirs. Before the English, French, and others arrived en masse in Rome in the 18th century, architectural painters had very often worked large canvases – the better to decorate large, local palazzi and villas.

Interestingly, Ghisolfi also plays a role in another of this Catalog’s pictures – a classicizing view of Alexander at the Tomb of Achilles. Authorship is given to a somewhat mysterious artist, currently called the Monogrammist GAE. Art historians posit this likely northern Italian painter was either the young Ghisolfi, or a later artist working in Ghisolfi’s style.

Figure 8. Hubert Robert, Figures Before a Ruined Temple, oil on canvas, ca. 1780?

Equally mysterious, though in different ways, is an attractive, unusually and carefully composed, highly accomplished, early 18th century canvas, which came to us with one appearance, and, after diligent restoration, has emerged looking very different. Newly revealed are startlingly-scaled figures, two rounds of early re-working, and a different format! Unknown, as yet, are the picture’s origins and authorship. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, a group of Neapolitan painters, working in their exuberant, singular late Baroque manner, pushed architectural fantasy painting in unexpected directions, with unusual lighting, scenographic and narrative content.

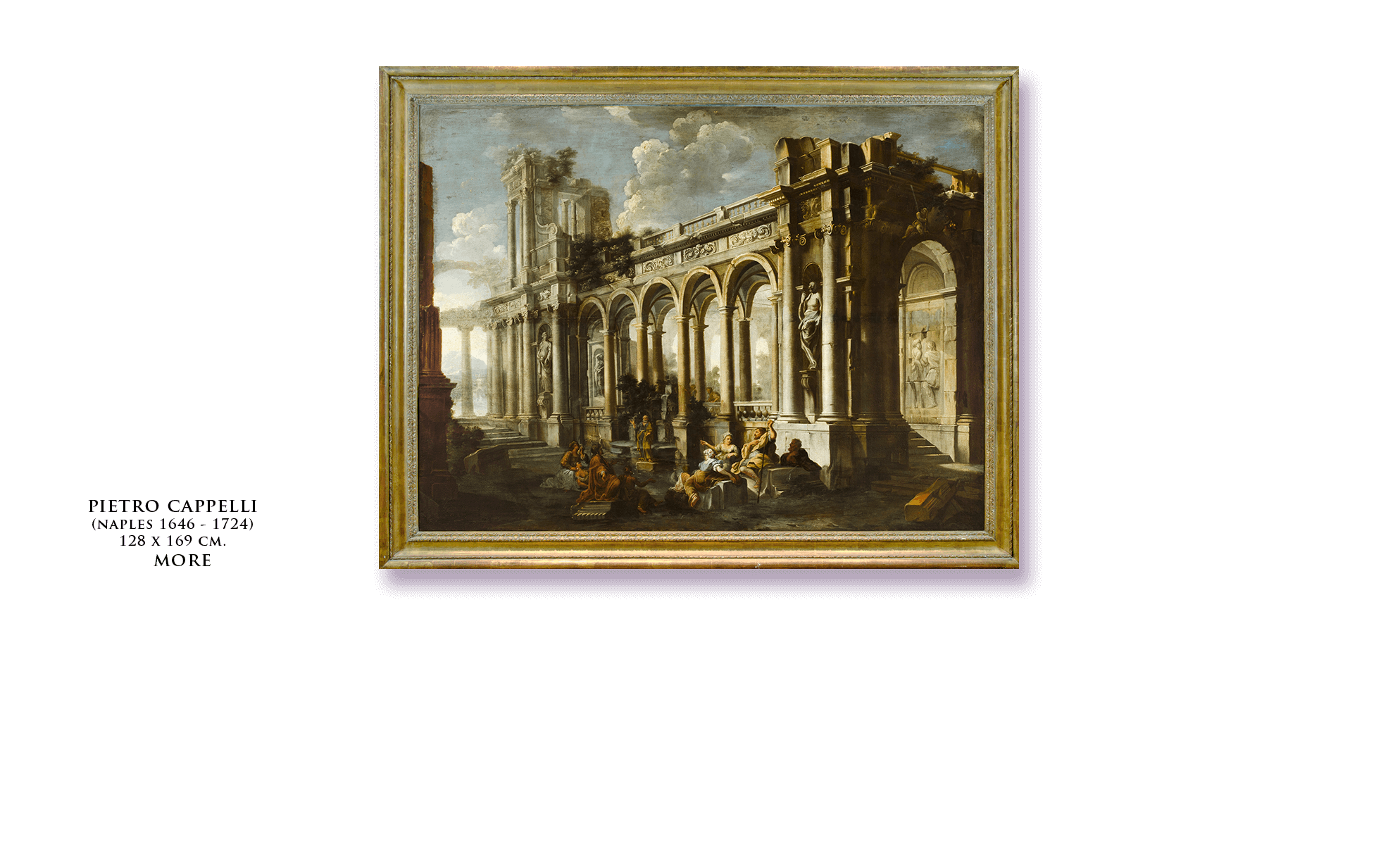

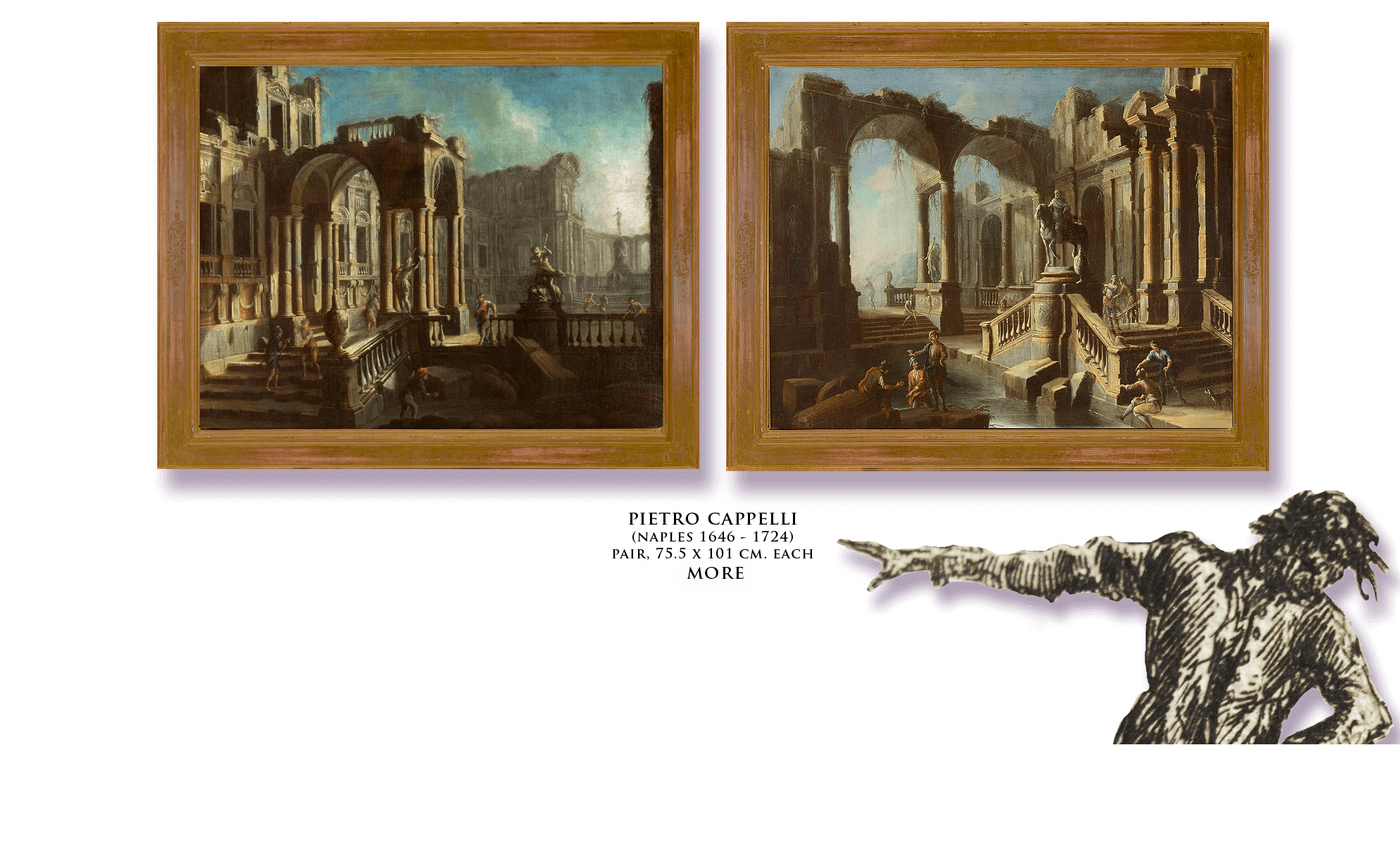

We earlier mentioned Gennaro Greco, “Il Mascacotta,” of whom Piraneseum’s Catalog includes a lovely, small, delicately-worked, perspectivally-accomplished imaginary view of a ruined temple by a seaport. Other Neapolitan vedutistas include Ascanio Luciano, a student of Codazzi’s (of whom we’ve a charming signed view from the 1690’s); and Pietro Cappelli, a slightly later painter known for his highly architectural fantasies.

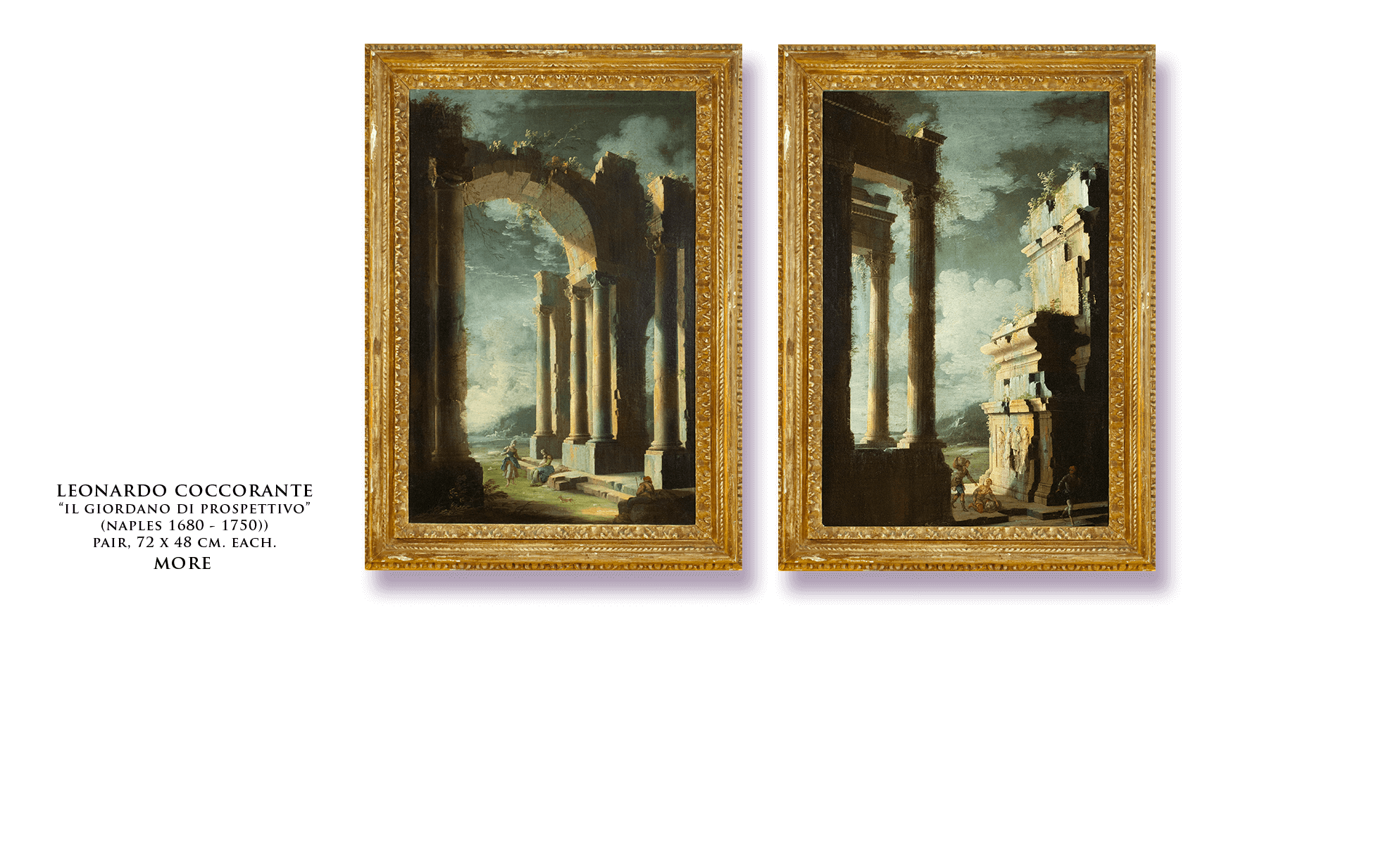

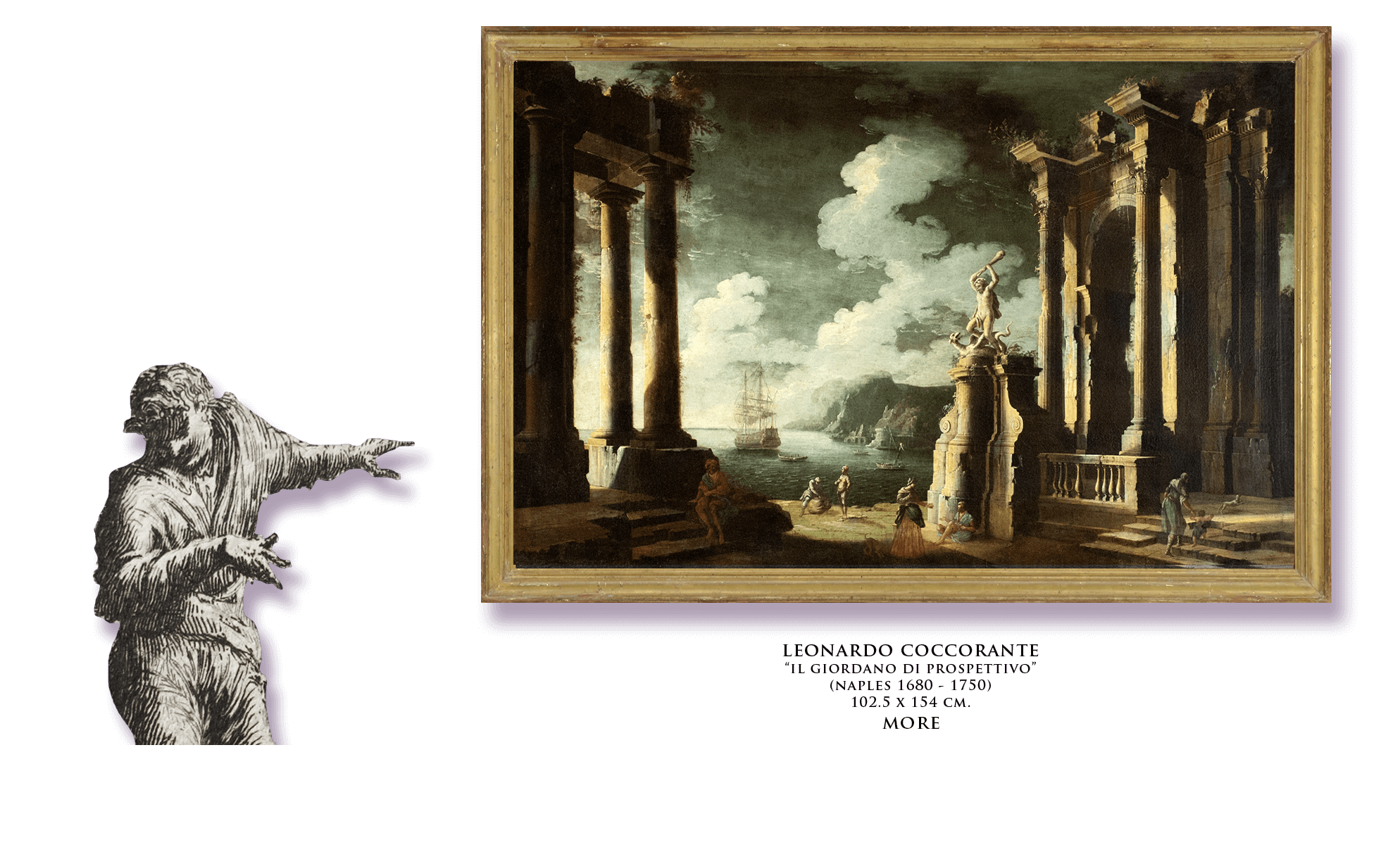

Perhaps the most distinctive of these artists, though, was Leonardo Coccorante whose signature, highly expressive, vedute portray ruins at twilight, bathed in moonlight, populated by shadowy characters and dark goings – on (fig. 7). The Catalog includes two pairs of pictures by Coccorante, as well as an impressively large and ambitious canvas.

Gian Paolo Panini, the Roman architectural painter inspired by Ghisolfi, and the most famous of Italian vedutistas, began his half century long career in Rome about 1715. He was a success from the beginning, his magnificent, carefully delineated pictures much esteemed by Grand Tourists. The Catalog includes two paintings by Panini, one a characteristic work of his late maturity, the other an unusual un-populated view from his youth. He was sufficiently successful that he employed a large workshop to assist in the production of his paintings.

Panini’s favorite member of that staff was a Frenchman, Hubert Robert (fig. 8), who went on to a career in Paris just as successful as his mentor’s in Rome. On offer is a lovely, small, Roman-inspired view by Robert.

Figure 9. Viviano Codazzi’s ca. 1660 painting of the Colosseum and Arch of Constantine with antique architectural models.

All these “names,” big and small, are held in the collections of fine arts museums around the world. The Catalog includes the particulars for each artist. Thus, while currently a quiet corner of the market in Old Master pictures, the phenomenon of 17th and 18th century Italian architectural paintings is very widely appreciated, shared, and valued.

Perhaps some work in Piraneseum’s Catalog, featuring accomplished pictures by the entire range of the most talented artists – the greatest “names” – who painted in this rich and historically important tradition, will come to form the cornerstone for your own collection of capricci, as they have for others, over the course of four centuries.

Considered alongside Piraneseum’s other offerings – antique architectural models (in their range of rich materials, including antique specimen marbles and alabasters, ormulu and dark-patinated bronzes), 18th century works on paper (by the likes of Piranesi, Guiseppe Vasi, and Marco Ricci), and antique architectural decorative arts – these paintings today, as they always have, contribute to forming interiors remarkably synchronous, engaging, distinguished and, if desired, not a little sumptuous (fig. 9).