Architectural History To Go

Figure 1. Highly finished ca. 1820 bronze model of Rome’s Lateran Obelisk, made by founders Hopfgarten & Jollage, is set atop a red and black granite base.

Not long ago, at a small sale outside of Philadelphia, we came across a large bronze model of what we felt certain was one of those ancient Egyptian obelisks which are such familiar monuments in the Roman cityscape. (There are more antique Egyptian obelisks in Rome than in Egypt). This model (fig. 1) was unfamiliar in some ways – unusually tall for a bronze casting, its hieroglyphics especially boldly, expertly, and apparently accurately rendered, with a base featuring lines and lines of Latin text which we couldn’t recall seeing before. These bronze elements were set atop a further base of red and black polished stone, also of a type we didn’t remember.

Never mind, though – this impressive miniature was very clearly of 19th century manufacture and we imagined the object’s mysteries would yield before application of sufficient research once we had it home.

For us, it is precisely these models’ mysteries, their intriguing, surprising histories and wide-ranging variety that is at the heart of their appeal and our on-going enthusiasm and fascination.

As collectors know, these miniatures are much more than simple replicas or tourists’ mementos. There is something about having before you, or holding in your hands, a two hundred year old, carefully crafted, architectural souvenir, something which provokes not just memories of a particular place, but also the breadth of one’s imagination. Through whose hands, and what places and circumstances, had this object passed on its two century long journey from Rome to California? Imagine Rome two hundred years ago; imagine California! Always, these models are, very nearly literally, transporting.

Eventually, transported to our desk in the San Francisco Bay Area, we placed that tall, bronze, Egyptian/Roman/Pennsylvanian/now Californian obelisk next to our iMac (talk about juxtaposition) and began the inquiries. At first, the monument was reluctant to give up its secrets.

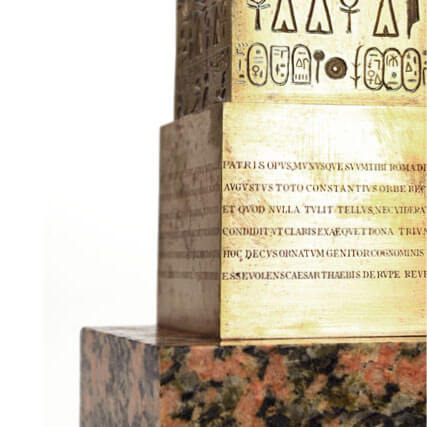

Figure 2. Detail of the base of the model shown in Fig. 1. The lines of Lateran text reflect the ancient appearance of the Obelisk, when it was brought to Rome from Egypt in 357 A.D., and installed in the Circus Maximus. The stone base is of Aswan granite, quarried in the 14th century B.C.

In search of the meanings of the Latin lines at the model’s base, we came to the late 16th century text, Rerum Gestarum qui de XXXI supersunt. The Latin, it developed, reflected the antique, no longer extant, inscription at the base of what is now, but wasn’t always, the Lateran Obelisk, Rome’s tallest. Let me explain. Originally erected at the Temple of Karnak in the 14th century B.C., the obelisk was brought down the Nile to Alexandria in the early 4th century A.D., at the direction of Emperor Constantinius I. In 357, the Emperor’s son, Constantinius II, had it moved to Rome and installed at the center of the Circus Maximus. The bronze model’s Latin inscription reflects its appearance in this period. Soon enough, of course, the Eternal City and the obelisk fell; the abandoned Circus, built on a swamp of sorts, filled with 20 feet of mud and debris.

A thousand years later (!), in 1587, Pope Sixtus V directed that the obelisk, lately rediscovered and which had broken into three pieces, be excavated and reassembled, on a new base, in the piazza fronting St. John the Lateran. The architect for this work, Domenico Fontana, recorded the antique inscription on the ancient Roman base, which he replaced with a new support featuring, naturally, a flattering dedication to his client, the Pope. Fontana also removed the bottom four meters of the obelisk, presumably for structural reasons.

In making our way through the old texts, we noticed references to the red granite from which that obelisk was carved. The Handbook of Ancient Roman Marbles (1894) notes this and others were fashioned from a stone called Syenite – “The quarries were situated about two miles from Syene, the modern Aswan.”

We were slow to realize what we had before us. Remember the model’s polished red stone base? Googling “Aswan red granite” brought images of this stone’s distinctive patterning, a match to that of the model’s base. Mustn’t some small portion of the twelve feet of the 3500 year old obelisk discarded by Fontana have found its way to this model? (fig. 2) In time, we found images of another identical model (these objects were always made in multiples), part of the collection of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, in Milan. Both ours and theirs sport red Aswan granite bases.

Figure 3. Among the earliest souvenir models is this olivewood, ebony, ivory, and mother of pearl replica of Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, fashioned in the late 17th century by Franciscan monks, and sold to well-to-do European pilgrims.

The authoritative volume on gold-finished, (gilded) bronze or ormulu – Vergoldete Bronzen (1986) – mentions this model, and attributes it to a pair of Prussian bronze casters working in Rome ca. 1820, Wilhelm Hopfgarten and Benjamin Jollage. In 1820, in Rome, might the discarded section of an Egyptian obelisk have proved a perfectly reasonable (and apropos) source for the base of a tourist’s souvenir? Every model tells a story, though the telling of some tales is made richer as we, the latest audience, participate in their unravelings.

The making of architectural models – miniature replicas of buildings, monuments, human-made places of all types – is an ancient, persistent phenomenon. Among the earliest of these appears in the Near East, in the 5th century B.C. and a thousand years later, in Europe. Architectural models are among the cultural artifacts of nearly all ancient civilizations (as well as those more modern).

However, the sort of architectural model that is our focus – replicas made for tourists, that is to say souvenirs – are a more recent development. By the third quarter of the 17th century, well after the discovery and excavation of many of Jerusalem’s holy Christian sites, Franciscan friars there began crafting multiple, highly-finished, olivewood/ebony/ivory/mother-of-pearl models of the city’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre. These expensive, elaborate replicas were purchased by especially well-heeled pilgrims, and carried home as mementos of visits to the Holy Land. (fig. 3)

At very nearly the same time, in 1670, Englishman Richard Lassels published his The Voyage of Italy, the first tourists’ guide to that destination, and the first to describe the journey a “Grand Tour.” Lassels traveled five times to Italy, and was a so-called “bear leader,” shepherding aristocratic youth, placed in his charge, on many months’ long visits throughout the country, then under the dominion of Habsburg Spain.

Figure 4. Ca. 1780 cork model of the ancient Roman Temple of Vesta, Tivoli. (Victoria and Albert Museum)

By the middle of the 18th century, among the variety of works and wares available to well-to-do Grand Tourists in Italy – including marble and bronze antiquities, Renaissance and later sculpture, canvases, and furnishings, and a range of more contemporary decorative objects and domestic accessories – were a variety of architectural models fashioned from cork, replicas of Italy’s and especially Rome’s, ancient, ruined, Classical monuments.

Architect Auguste Rosa, who lived in Rome from 1738-1784, is given credit for inventing the souvenir cork architectural model and for realizing the uncanny ways in which the small, irregular surface voids of cork suggest the textures of ancient marble ruins.

However, it was another Roman architect, Antonio Chichi (1743 – 1816), who understood the medium’s full (and commercial) potential. His 1786 catalogue lists for sale 36 different cork models – the Colosseum, Pantheon, a variety of temples, triumphal arches, theaters, tombs, etc. – at prices ranging from 15 to 168 ducats. Extensive collections of Chichi models are in the Art Academy in St. Petersburg, Wilhelmshohe Castle in Kassel, and Hessian State Museum in Darmstaat. (In order to see the Russian models, originally purchased by Catherine the Great, we were obliged to offer a small gratuity to the Academy’s superintendent – a fee more than repaid by the room after room of spellbinding Chichi miniatures.) (fig. 4)

The German Carl May (1747–1822), pastry chef to the Prince Bishop of Mainz, fashioned a wide range of cork models depicting Classical Italian ruins, and Gothic German monuments as elaborate table decorations for state occasions. Many of these are now in the Schloss Johannisburg in Aschaffenburg, Germany.

Rome, later in the 18th century, saw the production of souvenir architectural models in other materials as well. Felipe Coccunos and Guiseppe Volpate operated separate trades in porcelain and biscuitware which, among a variety of replicas, included Classical landmarks – triumphal arches and obelisks, etc. To date, we’ve located no surviving examples of these fragile objects.

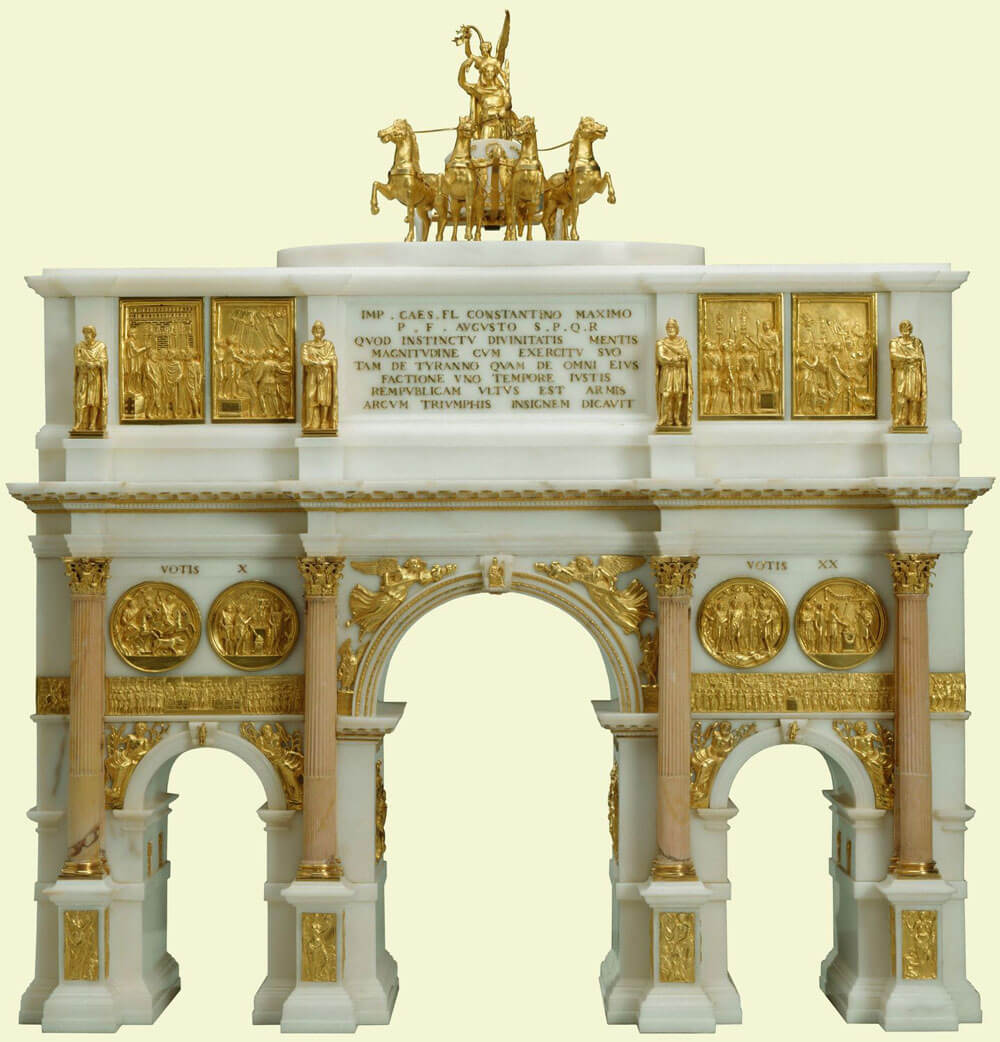

Figure 5. Ca. 1810 Carrara and giallo antico marble, with gilded bronze detail, model of Rome’s ancient Arch of Constantine, crafted by Giiovacchino and Pietro Belli. It was only by 1820 that the base of the Arch was fully excavated, thus the Bellis’ work was archaeological, as well as decorative. The four-horse chariot (quadriga) surmounting this monument had been a feature in antiquity, but was pulled down when Rome was sacked. (Royal Collection, Windsor Castle).

Working with more precious (and durable) materials, Roman goldsmith Luigi Valadier (1726-1785) assembled, often from sumptuous combinations of precious materials – including gilded bronze, lapis lazuli, porphyry, the rarest, most brilliantly-hued antique marbles, etc. – very highly-worked, apparently one-of-a-kind models of the city’s ancient monuments. As with other makers, these models formed only a small part of Valadier’s offerings of all species of decorative arts.

Among the greatest of these extraordinary objects is a group of several gilded bronze and antique marble models of Rome’s Trajan’s Column, produced for Pope Pius VI, as gifts for foreign heads of state, often with whom the Holy See was conducting delicate political negotiations.

In the first part of the 19th century, the Valadier workshop, then headed by Luigi’s son Guiseppe, produced very highly-wrought, one-off architectural models.

While our focus here is not on one-of-a-kind souvenir architectural models, it would be remiss not to mention the spectacular group of three miniatures of Roman triumphal arches, fabricated from marble and gold, over the course of seven years, in the very early 19th century, by Giovacchino Belli (1756 – 1822) and son Pietro (1780-1828). In 1816, these were brought to London, and offered to George IV for 3,000 guineas (the Prince Regent eventually parted with 500). Today, these models ornament Windsor Castle. (fig. 5)

Though our central interests are with souvenir architectural models produced in multiples, these were, almost always, only narrow segments of retailers’ wider inventories of decorative objects. Catering to Grand Tourists in Rome, in the later 18th century, the catalogue of bronze foundry Giovanni Zoffoli (1745-1805) offered five dozen cast miniatures of the most famous, often antique sculptural figures and groups. Of these, just one – a model of the ancient equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, atop its Michelangelo-designed base at the center of the Campidoglio, available for 40 soldi, might be counted architectural.

Figure 6. Accounts from the first part of the 19th century mention founders Wilhelm Hopfgarten and Ludwig Jollage’s gilded bronze model of the Arch of Constantine. As with others of their souvenir architectural replicas, this model portrays the landmark’s ancient, rather than modern appearance, here including the Arch’s long lost equestrian figures and quadriga atop the roof.

In 1785, the competing Roman bronze foundry of Francesco Righetti (1738-1819) purchased Zoffoli’s business; and in 1794 published a catalogue extending to nearly 10 dozen replicas of Classical statuary, or all types and scales. Of these, just one architectural replica, yes, of Signor Aurelius and his steed, almost certainly from Zoffoli’s mold – was among the offerings. Perhaps its price, raised to 45 soldi, reflects declining competition.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t until the 1804 arrival in Rome of highly-skilled Prussian bronze founders Wilhelm Hopfgarten (1779-1810) and Benjamin Jollage (1780-1837) that a wider variety of souvenir architectural models became available. The pair, who also cast work for famed Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1884), and created sculptures commissioned by German King Ludwig I, produced large, remarkably-detailed gilded bronze replicas of several Roman monuments – the Trajan and Antonine Columns, Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Monument and Arch of Constantine (fig. 6), as well as Egyptian obelisks in the Piazzas di San Giovanni Laterano and del Popolo. In this, they extended the tradition of finely-wrought, Roman architectural miniatures begun by Luigi Valadier and extended by the Bellis, while making these for a somewhat wider group. One no longer needed to be a king, general, or bishop to obtain a gleaming, gilded model of an ancient Roman monument. Beginning in the first quarter of the 19th century, and continuing forward, money (a lot of it) became sufficient qualification.

The firm’s high-quality production of architectural models was well-regarded from the outset, and both diplomats and Catholic church officials employed their miniatures as gifts.

“It is reported that Mgr. Ferrieri is about to go as envoy from the Pope to then Sultan. He carries with him the following presents; a gilt bronze model of the Column of Trajan; a magnificent table of mosaic work.,…”

Catholic Magazine (1848)

Figure 7. Why talented Prussian founders Hopfgarten & Jollage moved to Rome in the first part of the 19th century is, as yet, unknown. However, their accomplished work with bronze souvenir and architectural models was much remarked on at the time. These gilded bronze replicas of Trajan’s and the Antonine Column join a list of models including obelisks, the Arch of Constantine, and Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Monument in the Campidoglio.

At an 1870 concordat in Bavaria, the Pope presented the firm’s models of the Trajan and Antonine Column to his German hosts. A mention in the volume Rome in the 19th Century (1826) records the range and skill of the Prussians’ work. “Hopmartin (sic) – a remarkably ingenious German – executes models in bronze of the Triumphal Arches, Columns, Ruins, Ancient Vases, &c. of Rome. He has executed a bronze model of Trajan’s Pillar, with the whole of the bas-relief, accurately copied – an extraordinary work.” (fig. 7)

Hopfgarten and Jollage’s architectural models are in the collections of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Palazzo Pitti in Florence, and Munich Residenz (Piraneseum is fortunate to offer, as of this writing, several examples of the firm’s work).

In short order, almost of course, native Roman foundries took up casting souvenir architectural models of the city’s antique landmarks, though none reached the level of craft seen in the work of the Prussians. There was, though, no need of this. Ever burgeoning numbers of tourists later in the 19th century were increasingly of more modest means than earlier visitors. This meant a brisk trade in less costly souvenirs. Over the next half century, well into the 1870’s, tourists’ accounts of visits to the Eternal City mention bronze miniatures of the Pantheon and Colosseum, the Temple of Sibyl at Tivoli and Tomb of Cecilia Metella along the Appian Way, Trajan’s Column and the Arch of Constantine.

Here, a visit to a Roman souvenir shop in 1862 –

“I ask for mosaic breast pins – for every person must buy mosaic breast pins before leaving Rome. The proprietor rolls them out before me, a few hundred or so, large and small, pictured with every ruin and piece of statuary from the Coliseum to Pliny’s doves. “And does not signor want a bracelet, to accompany the pin? See! Here is a lovely article.” And I buy the bracelet. Then I must have the little bronze model of the Pantheon, of course.”

The Knickerbocker, December, 1862

Figure 8. An 1835 fire gilded bronze model of the façade of Rheims Cathedral, France, by Bavozet Freres et Soeur, Paris. Set on an inlaid rosewood base and fitted with a clock movement, this clock case reproduces the central features of the cathedral, including the Gallery of the Kings, with extreme fidelity.

At almost the same time as Berliners Hopfgarten and Jollage began realizing their remarkable, gilded bronze architectural models, there were parallel achievements in Paris. Beginning in about 1830, a small number of Parisian foundries began casting superbly detailed models, often in fire-gilded bronze (ormulu) of the facades of Gothic cathedrals – including Notre Dame in Paris, as well as Rheims, Rouen, and others – all fitted out as clock cases. (fig. 8)

It had long seemed to us a remarkable coincidence that these sorts of very highly-realized fire-gilded bronze souvenir architectural models began to be realized, nearly simultaneously, in Rome and Paris. We supposed some common ancestry.

It develops that Wilhelm Hopfgarten, along with his brother, had first taken up bronze casting in the family foundry in Berlin. Before setting out for Rome, where he arrived in 1804, Wilhelm stopped to study in, yes, Paris. While this period somewhat predates the emergence of gilded architectural models, and though there is no evidence of Wilhelm’s apprenticing in the foundries of manufacturers who went on to produce these models, there must, it appears, have been something in the Parisian water of the early 19th century that led in this direction.

A leading Paris maker, Bavozet Freres et Soeur, began business by 1823 and cast these sorts of models until at least 1847. At the 1834 ‘Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie Francaise’, the firm exhibited gilded bronze miniatures of the façades of both Rheims Cathedral and of Rouen Cathedral. Bavozet later made miniatures of Notre Dame de Paris, as well as another of Rheims, at a larger scale.

The fire-gilding process, with which these models were finished, involved coating the finished bronze casting with an amalgam of mercury and gold, then applying a torch, which caused the mercury to vaporize, leaving behind a thin gilt layer. The airborne mercury, of course, was terrifically toxic, sufficiently so that this method of gilding was banned in France, beginning in the 1830’s.

Figure 9. Ca. 1835 fire gilded bronze model of the façade of Rouen Cathedral, France, by Bavozet Freres et Soeur, Paris. The very highly detailed clock case was sold to the famed clockmaker Breguet (then of Paris, now of Vallee de Joux, Switzerland), who added their esteemed clockworks, and sold the clock later the same year.

Of these earlier 19th century French models, a particular favorite of ours is a remarkable, fire-gilded bronze replica of the façade of Rouen Cathedral. When we found this (it had resided, for a very long time, in an English barn) we noticed it seemed to retain its original works, which were engraved “Breguet a Paris No. 242.” Founded in Paris in 1775, the well-known horologists are now a Swiss company. We wrote to the Breguet Museum, still in Paris, inquiring after our timepiece and, (one is tempted to say) like clockwork, received their reply, including that the case had been manufactured by Bavozet and the clock sold on April 4, 1835, for 550 French francs to a Monsieur George Irby. (fig. 9)

Later 19th century French bronze souvenir architectural models are quite differently turned out, almost always in dark patinas, and just as often representing that small set of Parisian landmarks including the Colonnes Vendome and de Juillet, Luxor Obelisk, and Arc de Triomphe. As in Italy, these objects were part of the general trade in tourists’ mementos.

“Close to our dwelling is the Place Vendome, in the Rue de la Paix, one of the wide streets with elegant shops, so showy and attractive to the eye, that I loiter along it whenever I go to the garden of the Tuileries, to examine some novelty in art or manufacture; the bronze model of the obelisk at Luxor, jewellery, fake diamonds and other paste reproductions of precious stones…”

A Summer Jaunt Across the Water, John Jay Smith (1846)

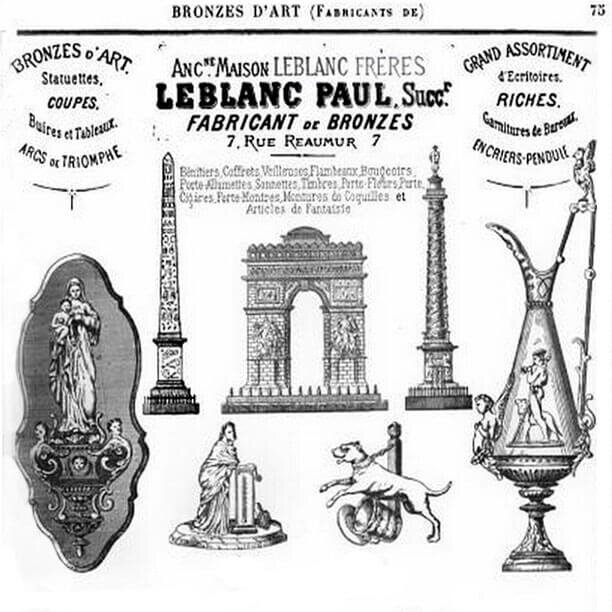

With these souvenirs, no firm was more prolific than the Parisian Leblanc Freres.

The 1859 Annuaires et Almanaches du Commerce describes the firm’s wares including “…coupes, statuettes, colonnes, arcs de triomphe, objets d’art…” and an illustrated advertisement in the 1878 Annuaire du commerce Diderot – Botin pictures “Ancienne Maison Leblanc Freres’ ” bronze models of the Luxor Obelisk, Arc de Triomphe, and Colonne d’Austerlitz, among a variety of decorative objects. (Not shown is the firm’s model of the Colonne de Juillet) (fig. 10)

Figure 10. A portion of Le Blanc Freres advertisement in an 1878 Annuaire du Commerce Didot – Boten, picturing the firm’s replicas of the Arc de Triomphe, Luxor Obelisk, and Colonne Vendome. Not shown is Le Blanc’s model of the Colonne Bastille. (It has been suggested, though not yet confirmed, that the firm also produced replicas of Trajan’s Column in Rome).

It is occasionally claimed the firm joined with the famed Barbedienne foundry, following founder Ferdinand’s death in 1891. However, it appears this may be a misunderstanding, based on the coincidence of Barbedienne’s nephew’s (and successor’s) name, Gustave Leblanc.

Of an entirely different order than these fancy tourists’ souvenirs are the spectacularly large and impressive bronze models of Paris’s Colonne Vendome, cast in the 1830’s and later. While Hopfgarten and Jollage’s very fine early 19th century, bronze replicas of Rome’s Trajan’s and Antonine Columns reach to two-and-a-half feet tall, these equally highly-realized Parisian miniatures of ‘Napoleon’s Column’ rise to four, five, and six feet in height. As well, to an extent not yet fully understood, these large models appear to have participated in the history of the monument they so carefully replicate.

A 2003 Sotheby’s sale of a 69” tall, mid-19th century, bronze replica of the Vendome Column yielded a winning bid of $176,000, and in short order others were offered for sale. Among these were two models once owned by Prince Victor Napoleon, also called Napoleon V; son of IV, grandson of III, etc. Because III (Charles Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte) lived during the period these models were cast, and because of the important role he played in the Column’s history, it seems likely these two replicas descended from him.

Before pursuing the histories of these remarkable models, though, we should remember something of the history of the Column itself. When we think of monuments, we think of solemn, immutable constructions, persisting across centuries. The Vendome Column, though, over time has proved a very variable monument. Even its name isn’t fixed. It has been called the Colonne d’Austerlitz, Colonne de la Grande Armee, Colonne Vendome, and of course, Napoleon’s Column.

Figure 11. An apogee of 19th century European souvenir architectural models, this 6’-0” tall bronze model of Paris’ Colonne Vendome was assembled by famed French medailleur Nicolas-Guy-Antoine Brenet from more than 100 very highly-finished castings. This model’s detail rivals that of the monument itself. This scarce example was once owned by notorious aesthete Carlos de Bestigui, and stood at the center of his library at Chateau de Groussay.

It is very closely modeled on Rome’s Trajan’s Column; the suggested equivalence of the two emperors is hardly subtle. Built in 1806 through 1810, the Colonne was originally surmounted by Antoine-Denis Chaudet’s (1763-1810) statue of Napoleon in imperial Roman costume, including toga, laurel wreath, sword, and, in his left hand, a small statue of Victory. This version of the monument endured all of four years! In 1814, Roman Napoleon was pulled down, for political purposes, and replaced with a flag, which remained for a year, before being replaced by another flag. In 1833, for political purposes, Napoleon was retuned to his perch; this time rendered, by sculptor Charles Emile Seurre (1798-1858), as the tricorn-hatted, hand tucked in vest, “Petit Corporal”.

By the 1860’s, Napoleon III (1808-1873) – remember him? Victor Napoleon’s grandson, then ‘Emperor of the French’, is said to have thought his grandfather’s statue demeaning. In 1863, for political purposes, the Little Corporal was replaced by a figure of Napoleon as, almost of course, a Roman emperor, a statue very freely adapted, by sculptor Augustin Dumont (1801-1884), from Chaudet’s original.

In 1871, for political purposes, a crowd of Communards led by painter Gustav Courbet, pulled down the Column, which by 1874, for political purposes, had been fully restored, and is the monument seen today.

To an extent unmatched by other landmarks, souvenir models of Napoleon’s Column reflect its ongoing permutations. The history of the greatest of these models, a signal accomplishment of 19th century architectural miniatures, began in 1810, when the monument was just complete. (fig. 11)

It was then that Nicolas-Guy-Antoine Brenet (1770-1846) conceived the idea of an astonishingly accurately detailed, six foot tall, cast bronze replica of the Column, at a scale of 1:24 – a project that would occupy him, in various forms, for the rest of his life. By 1828, Brenet had arranged with the sculptor/finisher Clauteaux to begin fashioning the cast bronze elements from which the model was to be assembled. By 1833 (remember, there were then plans afoot for sculptor Seurre’s “Petit Corporal”), Brenet took the precaution of casting both Seurre’s and Chaudet’s figures of Napoleon. At the same time, Brenet arranged for State sponsorship of the project, insuring it’s success.

Figure 12. Produced by W. F. Woodington, sculptor of one of the bas-reliefs at the base of Nelson’s Column, this dark patinated bronze model of the London monument, one of 25 cast by Mssrs. Franchi, was made in 1868 for select members of the City’s Art Union. The Art Union’s purpose was described this way – “to aid in extending the love of the Arts of Design, and to give encouragement to Artists…” – worthy goals then, and now.

When the model was, at last, completed, it proved something of a sensation – the King, Louis Philippe, purchased an example for the Paris Musee de la Monnaie, while others were acquired for various State collections, including Paris Musee de l’Armee. By 1835, the well-heeled might purchase Brenet’s remarkable model in the store of famed decorative bronze dealer Pierre-Victor Ledure, in the Rue Vivienne. Equally remarkable was the price of these models – 6000 French francs. After Brenet’s death in 1846, there were subsequent editions of the model, in 1856 and, perhaps 1870. Outside of replicas held in public institutions, we have located very, very few examples.

Somewhat more numerous are a group of large, dark-patinated bronze models of the Vendome Column, all of which feature Seurre’s “Petit Corporal”, and so must date from between 1833 and 1863. The earlier years in this range, before Seurre’s figure fell from favor, are perhaps the more likely. Though significantly lesser achievements than Brenet’s model – they’re without the latter’s remarkable detail and craft and may, in fact, have been “inspired” by Brenet’s – these replicas are fully formidable. That 2003 Sotheby’s sale of a Vendome Column model, reaching $176,000, was for one of these “lesser” replicas.

As of this writing, we are fairly thrilled to be able to offer examples of both the Brenet and other, related, large-scale models.

The tradition of carefully-crafted, French bronze souvenir architectural models persisted into the 1890’s, when it was overcome by lower quality work cast in so-called white metal – a zinc rich alloy. Interestingly, despite the relative availability of a range of local, colorful, easily-worked stone, France, unlike Italy, is without a history of souvenir architectural models in this material.

Equally unexpected is the spotty production of 19th century architectural replicas in the United Kingdom. It was, after all, the English who were the predominant Grand Tourists, and who possessed such prodigious appetites for these mementos. Among the greatest of the multiply-manufactured British efforts is a two-foot tall bronze model of London’s Nelson’s Column, cast in 1868 for the Art Union of London, an organization devoted to popularizing Art. This replica was produced by sculptor W. F. Woodington, who had shaped one of the four bas-reliefs at the monument’s base. (fig. 12)

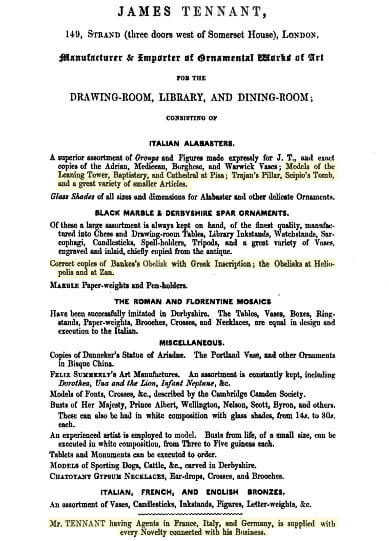

Twenty years earlier, geologist James Tennant, on The Strand in London, advertised, among a variety of decorative arts, “Models of the Leaning Tower, Baptistery, and Cathedral of Pisa; Trajan’s Pillar, Scipio’s Tomb, and a great variety of smaller objects, all made, says the notice, in “Italian Alabasters”. Thus, for the very frugal tourist, it was no longer necessary to visit Italy in order to display mementos of the voyage. (fig. 13)

Also advertised are a more singular group of models – miniature monuments fashioned from English stone – Derbyshire black marble and Derbyshire Spar, also called Blue John. Available replicas included “Correct copies of Bankes’s Obelisk with Greek Inscription; the Obelisks at Heliopolis and at Zan. The first of these, known today as the Philae Obelisk, was brought from Egypt to England in 1821, and caused sufficient excitement to occasion Tennant’s and others’ souvenirs.

Figure 13. Advertisement for James Tennant in an 1848 issue of Elementary Treatise on Mineralogy. His shop, its upmarket London address listed as 149 Strand, offered models of Roman monuments, including ‘Trajan’s Pillar’ and ‘Scipio’s Tomb’; the range of Parisian landmarks; two Egyptian obelisks, and another – ‘Banker’s Obelisk’- already in England.

Resurgent interest in Egyptian obelisks, and more lavish productions of Derbyshire black marble models, and others turned out in brass and tin, accompanied the 1878 arrival in London, from Alexandria, of Cleopatra’s Needle.

Tennant had apprenticed to among the earliest dealers in Derbyshire marble models and other ornaments, John Maure, who offered, by 1829, “correct copies of Egyptian Obelisks”.

Many of Maure’s and others’ black Derbyshire marble obelisk models feature accurate representations of the monuments’ hieroglyphics. Unlike similar Italian marble replicas of this period, whose Egyptian characters are carved, this detail in English miniatures is acid-etched into the stone; and the effect is more graphic than fully three dimensional. Maure and others prepared intricate stencils, which covered the polished black marble, protecting some areas, allowing fluoric or muriatic acid to coat and dull other surfaces. The stencil was then removed, revealing the etched pattern of hieroglyphics.

And yet, almost of course, the 19th century’s most accomplished, satisfying stone souvenir architectural models are, very nearly always, Italian.

“I found a city of brick and left it a city of marble”, boasted Caesar Augustus (64 B.C. – 14 A. D.). His feat is the more remarkable because, “as a matter of fact, there was no marble anywhere near Rome.”

Henry Pullen, Handbook of Ancient Roman Marbles (1894).

What, then, were the origins of the marble in Augustus‘ marble city? The answer, staggeringly (and with exceptions), is that, two-thousand years ago, this stone was quarried at the far reaches of the Empire – Greece, Turkey, Tunisia, Egypt, etc., etc. – then brought by ship to Rome. For example, the Roman marble today described as giallo antico ( yellow-hued stone) was originally excavated, from the 2nd to the 6th centuries, in ancient Numidia, a Roman province in North Africa. Likewise, the Roman stone now called verde antico *(a green-veined material) was brought to ancient Rome from Casambala, near the Greek city of Laressa. (Though almost always described as a marble, verde antico is, in fact a serpentine.)

What, you may ask, does the history of ancient Roman building materials have to do with the city’s 19th century stone souvenir architectural models? Remarkably, almost without exception, these slight tourists’ monuments are fashioned from antique marbles – which is to say from stone originally quarried two millennia ago in places at the Empire’s edge, and brought by ship to the Eternal City, where it formed the very fabric of ancient, Imperial Rome. (fig. 14)

Figure 14. A ca. 1800 Roman architectural model of an idealized temple. This lavishly-wrought object, including a variety of antique specimen stones – giallo antico, rosso antico, and Egyptian alabaster, all quarried far from Rome, millennia ago – portrays not a particular landmark, but a type of structure, the circular-planned temple, a constituent part of Classical Architecture, from the tholos of ancient Greece to Bramante’s Roman Renaissance tempietto.

Eighteenth century historian Edward Gibbon, with characteristic Enlightenment precision, fixed the date of Rome’s fall as September 4, 476, the day the last Roman Emperor was removed from office. In fact, as it often is with failing civilizations, the end of the Roman Empire was a drawn out affair. Beginning in 410, and over the course of the next 150 years, the Eternal City was consecutively sacked by the Visigoths (410), Vandals (455), and Ostrogoths (546). Other sackings, in 846, 1084, and 1527, followed; and Rome lay, literally, shattered.

The beginning of the 17th century saw the rise of a new line of tradesman – the scarpellini, or stonecutters – whose work was fashioned from the profuse shards of ruined Rome. By the first part of the 19th century, and the unprecedented influx of tourists to the Eternal City, much of their production was focused upon souvenir architectural models.

“There is at Rome a profession connected with the arts, that exclusively belongs to its peculiar character or virtu… The Scarpellini are workers in marble and pietradura, who imitate in little the most exquisite forms, and most noted monuments of antiquity… Not a square inch of rosso antico or of oriental alabaster is rooted up in the gardens of the Caesars, by the parasol of an English dilettante, but it is instantly carried to the Scarpellini... and it may happen that the fragment of a pedestal on which a Titus has leaned will figure as a presse-papier on an English dressing-table, or be preserved in the model of the tomb of Scipio, or the sarcophagus of Cecilia Metella.”

Italy (1821)

Though, in part, produced during the same period and of the same materials, the scarpellini’s work is very different from the one-of-a-kind, very fine and elaborately turned out, late 18th century souvenir models produced by Roman goldsmith Luigi Valadier, his son Giuseppe, the Bellis, Hopfgarten and Jollage, etc., whose miniatures we discussed earlier. Not fashioned for princes or bishops, the scarpellini’s mementos were made for tourists of more modest means.

Figure 15. “ My companion scooped an ample harvest of antique monuments reduced to citizen proportions. He bought two Coliseums, one Arch of Titus, on Trajan’s Column, four obelisks, and one Tomb of the Scipio” Rome of Today (1861).

This is not to say, at all, that their work is unskilled. The highest examples are substantial achievements. Sufficiently talented scarpellini graduated their profession, becoming sculptors and architects. Francesco Borromini (1599-1667), mad genius architect of the Roman baroque, and famous thorn in the side of his creative mentor Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), began as a scarpellino.

For much of the first part of the 19th century it appears Rome’s stone cutters were the leading merchants of the city’s marble souvenir architectural models. Their work in this period is often made from out-of-the-ordinary antique stones; including those marbles more brightly or deeply-hued – rosso antico, verde antico, nero antico, etc., in addition to materials less rare – giallo antico, some alabasters, etc., – which predominated in the century’s second half.

“Another set of ateliers, almost worthy of the name of studi, are those of the Scarpellini, who are entirely occupied in carving the small fragments of rare marbles, with which the soil of Rome abounds, into miniatures models of Trajan’s Column, the Arch of Severus, the Sarcophagus of Agrippa, or any other relic of Roman greatness…”

Rome and Its Surrounding Scenery, William Bernard Cooke, Henry Noel Humphreys (1840)

Near the Villa Borghese is Via Scarpellini, and we imagine this street was once a center in the stone souvenir trade.

By mid-century, the scarpellini’s production was offered alongside other sorts of souvenirs. This account is from American in Rome (1863).

“Mr. Bourne, after carefully examining the usual yellow marble (giallo antico – ed.) model of the column of Trajan, the alabaster pyramid of Caius Cestius, the verde-antique obelisks, the bronze lamps, lizards, marble tazze, and paste gems of the modern-antique factories, the ever-present Beatrice Cenci on canvas, and the water-color costumes of Italy, made a purchase of a Roman mosaic paperweight, wherein there was a green parrot with a red tail and blue legs….”

A Handbook of Rome and Its Environs (1888) mentions two merchants, very near each other, “Boschetti, 74, Via Condotti, has a large assortment of modern bronzes, marble models of ancient edifices, bronze statues…” and “Giannini, 77, Via Condotti, for bronzes and copies of buildings in marble.”

Though these sorts of wide-ranging souvenir stores were to become the rule in Rome, and remain so today, other shops in this period hewed to the scarpellini’s wares.

“Now,” said the American, “I should like to buy some little souvenirs in marble to put upon the etageres with the shells and stuffed birds.”

The faithful servant, who followed us like our shadow, conducted us to the mosaic-worker, the marble-cutters, the cameo-engravers, the turners of hard stones. My companion reaped an ample harvest of antique monuments reduced to citizen proportions. He bought two Coliseums, one Arch of Titus, one Trajan’s Column, four obelisks, and one Tomb of the Scipios. (fig. 15-ed.)

Rome of Today (1861)

Figure 16. Three late 19th century Roman architectural souvenirs, carved from Italian alabaster from Volterra, including (l. to r.) ruins of the Temple of Castor & Pollux, Saturn, and Vespasian.

Remarkably, for a profession historically reliant upon ancient fragments of Roman ruins, stone cutters’ shops persisted into the early 20th century.

The industry of the scarpellino is still a thriving one in Rome and many are the queer little shops in the Via Sistina…

What Rome Was Built With, Mary Parker (1907).

In fact, by the close of the 19th century, their stores of antique marbles largely exhausted, some scarpellini were reduced to turning out souvenir architectural models in recently-quarried Italian alabaster. This stone, plain white, granular, and too soft to polish or take intricate detail – is no luxe material and offers only an echo of their richly textured, lavishly-worked predecessors. And yet, do these modest models exercise our imaginations any less vigorously? (fig. 16)

In hardly any instance was the source of the scarpellini’s materials a mystery. Often, it was the very opposite, and for much of the 19th century, tourists descents upon Rome operated similarly to those earlier visit by the Visigoths, Vandals, and Ostrogoths. There is this description, from A Catalogue of Pictures, Statues, Busts and at Hendersyde Park (1859):

“…a small Tazza (is) formed from marbles of the Ruins of San Paolo on a pedestal of the Ruins of the Tempio di Romolo. There is also a smaller Tazza of Giallo Antico from the Colosseum and another of Brescia from the Monte Palatino, also a fragment of the Porte Trajana at Ostia with some letters engraved on it and another of fine Giallo Antico from the Palazzo dei Cesari… On the Card Table is a small alabaster Model of the Leaning Tower of Pisa…”

Nineteenth century Roman stone souvenirs of all types, architectural models included, are often enough carved from the very monuments they cause us to remember. The effect is not very different from that of the Roman church’s saintly relics. Talk about synecdoche!

Figure 17. This impressively-sized (80” high), ca. 1856, marble, bronze, silver, and terra cotta model of the Colonna dell’Immacolata, adjacent to Rome’s Piazza di Spagna, is turned out in a profusion of sumptuous, richly-colored stones. Evidence points in the direction of this being a model presented by the monument’s architect, Luigi Poletti, to his client and the project’s sponsor, Pius IX.

Naturally, the greatest predations upon Rome’s ancient fabric were worked by the Romans themselves. For a thousand years, until the mid-18th century, the Papacy, among others, operated the Colosseum as a quarry – the source for Michelangelo’s and Fontana’s and Bernini’s and other great architects’ sensational, surpassing work at St. Peter’s, and other unidentified, projects. Today’s Colosseum, enormous as it appears, is scarcely a third of its original size.

A much more modest use of ancient Roman marble was with the occasional early to mid-19th century production of models of architect’s proposals, replicas of future monuments, rather than those from antiquity. Scarce, these miniatures, like those turned out by Luigi Valadier and others a half-century earlier, often employ a wide variety of antique marbles, to achieve maximum decorative effect. This use of a polychrome set of alluring antique stones – specimen marbles – mirrors other decorative objects in this period, especially tabletops and mosaic work.

(What happened, though, to the majority of the ancient marble brought to decorate Rome, with which Augustus transformed the “city of bricks”? In an irony of epic, even Imperial scale, over the course of centuries, Caesar’s marble was burned to produce quicklime, a central ingredient of mortar for, yes, brick, with which the Eternal City was, again, remade.)

Current offerings include an especially impressive example of this deluxe form of mid-19th century Roman architectural model (fig. 17). This very tall (80 inches high) replica of the Colonna dell’Immacolata is formed from no fewer than sixteen different types of marble and alabaster, as well as cast silver and bronze decorative panels, and sculpted terra cotta figures. Because the Colonna, completed in December, 1857, differs in subtle ways from this model (especially in the proportion and detail of the base), it seems clear this replica is earlier, though no earlier than 1855 when the monument’s architect, the Classicizing Luigi Poletti, was commissioned by Pius IX. It is not at all unlikely that the architect employed this model while presenting his plan to the Pope. Another very similar model, in the collection of the Museum of St. John the Lateran (originally in the adjacent Pius IX Museum) in Rome, is more accurate and, therefore, likely post 1857.

Our focus on the variety of 19th century Roman souvenir architectural models ought not obscure that, in this period, these sorts of mementos were produced elsewhere in Italy. Unsurprisingly, the history of these “other” Italian miniatures begins much later than that of their Roman cousins – the earliest appear to date to the 1840’s – and the rich variety of bronze and marble characteristic of Roman models is replaced by a single material – alabaster.

Figure 18. Four towers, all leaning, (Torre Pendente di Pisa, in Italian) all from alabaster (alabastro, in Italian) whose dates of manufacture correlate inversely to their size. The smallest was carved before 1850, the out-sized souvenir, to the left and largely out of frame, is ca. 1900.

Over time, we have seen mid and late 19th century alabaster miniatures of monuments ranging from the pair of Venetian columns crowned by St. Theodore and the Lion of St. Mark to La Lanterna, the lighthouse emblematic of Genoa.

A much more substantial, though not nearly Roman, history and tradition of souvenir architectural models unfolds, almost of course, in Pisa (fig. 18). The city’s tilting bell tower, duomo, and baptistry, all so picturesquely arranged in the Piazza dei Miracoli, are the usual subjects of miniatures, almost always in alabaster, beginning, it seems, by the 1830’s.

Some words on alabaster; a familiar, sometimes deceptive material. When we think of tiny Towers of Pisa fashioned in this medium, we think of the usual bright white stone, slightly rough to the touch, with a matte finish, never highly polished. This is so-called “modern alabaster” – a hydrated sulphate of lime – quarried in Volterra, in the province of Pisa, just an hour’s drive to the south. “…it is necessary to observe that the modern alabaster of commerce is a totally different substance from that employed in Roman decoration,” observes the Handbook of Ancient Roman Marbles (1894).

Ancient Roman alabaster, often called “Oriental alabaster”, was brought from Egypt and Algeria; the material – a carbonate of lime – harvested from stalactite caves! Oriental alabasters, unveined though often delicately striated, are very often subtly (and, rarely, brightly) colored in oranges and tans, and, therefore nearly as often mistaken for marble.

Unfortunately, for clarity’s sake, there is more to the story. “Modern alabaster”, it develops, is hardly a modern material, nor is it always that familiar, grainy, bright white stone. The quarrying of alabaster at Volterra began 4,000 years ago, and was a substantial industry in the time of the Etruscans. And the commonplace white stone is, it develops, one of 52 varieties of Volterran alabaster. In fact, true alabaster is found nowhere else on earth, claims Stone Magazine (1895). Oriental alabaster, it seems, is a form of marble. Enough, though, with this lesson in mineralogy.

Figure 19. Three Italian alabaster models of Pisa’s Baptistry of San Giovanni. The mid-size souvenir, while carved in Italy, was sold at the London mineralogy shop of John Maure, probably ca. 1830. The very large (17” high), carefully-carved model to the left, while unsigned, is similar to the work produced ca. 1860 by the Pisan firm Huguet and van Lint, who also specialized in photography.

Among several sculptors’ shops in Pisa, the leading was that of M. Huguet and Van Lint, who advertised extensively in English in tourists’ guides. Theirs, it appears, were the most ambitious and impressively turned out models, including startlingly large, meticulously-crafted miniatures of the Baptistry, among other subjects. These are fully comparable to the best of Roman antique marble production in this period. In the later 19th century, miniatures of monuments in other parts of Italy, including Rome, may have been carved in Volterra and shipped around the country, and, very possibly, exported to other countries.

This spectacularly large, zealously-detailed model of Pisa’s Baptistry which, though unmarked, is characteristic of the van Lint studio (fig. 19), is by far the largest we’ve encountered, made, of course, in several types of Volterran alabaster.

Handbook of Ancient Roman Marbles (1894) observes of alabaster from Volterra, “It is waxy in texture, and too soft to take a high polish like marble,.” Our Baptistry model appears this way, and Stone Magazine (1895) reveals the secret – “An artificial polish is given by the application with a woolen cloth of a paste compounded of bone-dust and common soap.” Good luck locating this compound in your local hardware store!

We’ve seen a large, richly orange-hued model of Pisa’s Chiesa della Spina, signed by van Lint and dated 1862 – an example of work in scarce agatized Volterran alabaster.

In the later 1840’s, as we’ve noted, James Tennant, London mineralogist and “Manufacturer & Importer of Ornamental Works of Art for the Drawing-Room, Library, and Dining-Room”, advertised alabaster “Models of the Leaning Tower, Baptistry, and Cathedral at Pisa”, while noting his Italian agents supplying “every Novelty connected with his Business”. Tennant carried on the business of his deceased mentor, John Mawe, at the same location, 149 Strand, London. Perhaps van Lint, savvy with English clientele, was among his agents; or was it some more obscure shop in Volterra?

Figure 20. This group of Volterran alabaster souvenirs of Pisa – the tower (actually, campanile or belltower), Cathedral and Baptistry of San Giovanni – was collected by a member of the Cavendish family and brought to the family home, Chatsworth House, where they are first recorded in an inventory of 1892.

There has been uncertainty over how long the phenomenon of modern alabaster souvenir architectural models persisted. A recent sale of furnishings from Chatsworth House, North Derbyshire, included a relatively modern alabaster miniature of the Pisan bell tower and Baptistry of San Giovanni (fig. 20). This object is included in an 1892 Chatsworth Inventory (though not earlier); and the 1890’s and first decade of the 20th century seem both an apogee and termination point of this type of souvenir.

Of a different order than the Pisan souvenir models, though from the identical, modern material, is a recent discovery – a very large, bright white, Volterran alabaster miniature of Florence’s Duomo, campanile, and baptistery, the finely-carved building set on a slab of white, Italian Carrera marble. When first examining this carefully-made, unusually accurate miniature, we were puzzled by the very plain, nearly detail-less façade of the Duomo, so incongruous with the balance of the replica. Had the original façade been damaged, then clumsily replaced? No. Our instincts here were embarrassingly far off the mark.

In fact, the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence’s cathedral, the early Renaissance triumph topped by Brunelleschi’s famous dome, featured a rough, unfinished façade well into the second half of the 19th century! It was only in 1876 that work began to finish the façade, which was completed in 1887. What this history suggests, of course, is that our model of the Duomo reaches back to the 1870’s.

Like Pisa, Florence is close to Volterra, just an hour-and-a-half to the southwest. Leading Florentine alabaster and marble sculpture studios in the mid-19th century included those of Pietro Mannaroni; the Signori Fuilli, Lapini, Vichi, and Romanelli; Gallerian Bazzanti; and the Pisani Marble Works. It is likely one of these studios fashioned the large, meticulously-carved model of the Duomo, bell-tower, and baptistry.

Figure 21. This impressive (36” high), lavishly-detailed, bronze-patinated zinc model of sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch’s best-known and most ambitious work – Berlin’s Equestrian Monument to Frederick the Great – is a marvel both of design and foundry technique. Cast by the Berlin firm of Hermann Gladenbeck beginning, it appears, when the monument was completed in 1851, and for several years after that, this model was widely exhibited in the period’s international expositions, and copies found their way into a variety of museum collections.

Comprehensive discussion of 19th century European souvenir architectural models must extend beyond Italy, France, and England, though these countries’ production is the most abundant and most abundantly interesting. However, German architectural miniatures in the period, most often turned out in spelter – a zinc alloy, usually copper-plated or with a bronze patina though also, occasionally, in lead, brass and tin plate, include Berlin monuments – the Siegessaule, Friedenssaule in Mehringplatz, and cathedrals in Cologne and Strassburg – when this was a German city, before it became, as it is today, Strasbourg, part of France.

Among the finest of our 19th century architectural models is a reduction of Berlin’s Friedrich II Reiterdenkmal (fig 21.). Among the greatest works of the greatest 19th century German sculptor, Christian Daniel Rauch, this elaborate monument, completed in 1851, chronicles King Friedrich II of Prussia’s life (1712 – 1786). Spelter models were cast in three sizes (ours, 36 inches high, is the middle) by leading German foundry, Gladenbeck. Accounting for some of this model’s very high quality was Rauch’s direct participation in the casting process (the sculptor sent models to potential clients, among others).

There are, of course, examples of 19th century souvenir architectural models made elsewhere in Europe, as well as in the United States. In the 20th and now 21st centuries, however, as travel has increasingly become a popular phenomenon, much more democratic and accessible, the nature of souvenir architectural models has utterly altered. Gone are the large, elaborate, carefully wrought, yes, expensive figures of familiar landmarks rendered in rich, evocative materials. Their replacements are smaller, cheaper, indifferently made, designed to be carried home in suitcases sufficiently small and benign to pass through airport security and to fit beneath the airplane seat in front of you; rather than requiring crating, long voyages at sea, or over land.

Is this a loss? Yes. A loss, but also the latest, and likely not the last, chapter in the long history of these most evocative of architectural mementos.