Etchers & Engravers:

Murderers & Suicides

Figure 1. Detail, An Imaginary View of the Appian Way, Rome. Giovanni Battista Piranesi. This 1784 architectural phantasm pictures the road leading to Rome lined by sepulchral monuments piled one atop the other, reaching skyward. Along the road itself, travelers, barely as tall as the adjacent stone curb, scurry forward and into the distance.

Among the varied appeals of 17th and 18th century Italian capricci and vedute are the robust, vividly polychromatic lives of the artists who painted them. Leonardo Coccorante, painter of moonlit, ruined, sinister scenes populated by bandits and their prey, learned his shadowy art from a condemned Sicilian burglar, while a jailer’s assistant in a Neapolitan prison. Fellow Naples resident Gennaro Greco, whose disfiguring burns brought him the none-too-gentle nickname Il Mascacotta – he of the cooked face – enjoyed three beautiful wives, (simultaneously!) before falling to his death from a high scaffold while, naturalmante, painting. Other vedutistas were well, even royally born, enjoyed the company and patronage of kings, Popes, and assorted aristocrats, while plying a profession they conceived as gentlemanly.

The lives of many 18th century Italian architectural artists on paper – those working often in black and white – are, if anything, more colorful (though darker-hued) than their painterly cousins.

When we think of 18th century Italian architectural graphic art, we think of the surpassing images of ruined Rome by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720 – 1778). Why are Piranesi’s etchings so powerful? If the ruins are not quite so immense as he portrays them, nor the people quite so tiny, poignantly approaching insignificance (fig. 1), if ruins’ realities are less dramatic than this artist has them appear, there is, in his views, an unerring emotional accuracy. Piranesi’s are pictures of the ways those ruined places feel.

Yet, when we think of Piranesi, do we think of murder? This was what he unsuccessfully attempted with one of his teachers, Guiseppe Vasi (1710-1782). What trespass incited Piranesi’s homicidal rage? Vasi thought his combustible student had withheld certain secrets of the use of acid in the etching process.

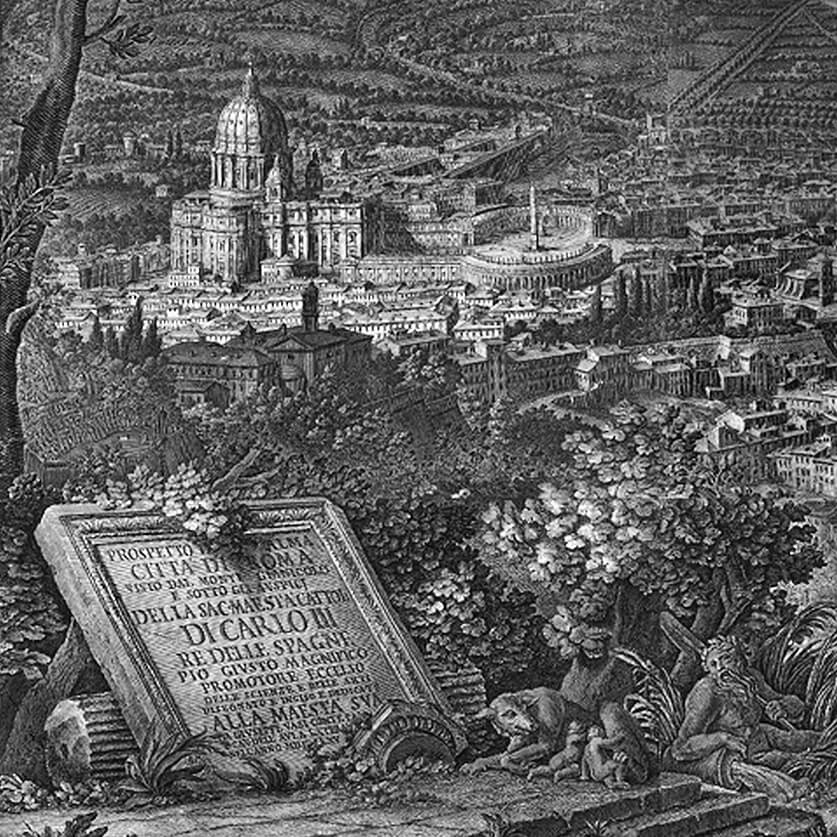

Figure 2. Details, Prospetto di Alma Citta di Roma dal Monte Gianicolo, Guiseppe Vasi. The title of Vasi’s 1765 etching appears carved into an ancient Roman tablet, at whose base the she-wolf provides for babies Romulus and Remus. An adjacent river god looks on, undaunted by the competing canons offered by the Church down the hill.

There were other provocations. It is recorded that Vasi also informed his hot-headed charge, “You are too much a painter, my friend, to be an etcher.” – an apogee in the annals of failed Art world prognostication!

(Had Piranesi succeeded, we would be without one of the signal achievements of 18th century etching – Vasi’s monumental view of Rome – Prospetto di Alma Citta di Roma dal Monte Gianicolo – etched across a dozen separate sheets, reaching a length of almost nine feet (fig. 2). And let’s not mention Piranesi’s threats on the life of the doctor attending his son Francesco, or his 1752 marriage to Angela Pasquini, whom he’d met five days earlier, while drawing amongst the ruins of the Forum, and whose dowry he immediately spent on copper etching plates.)

Possibly the roots of Piranesi’s uneven, murderous urges follow those of his artistic sources, including fellow Venetian Marco Ricci (1676-1730), an esteemed painter of hauntingly, achingly beautiful capricci, and in his final years, among La Serenissima’s first etchers. Piranesi scholars John Wilton-Ely and Arthur M. Hind trace direct lines of influence to the older artist, Ricci.

In Born Under Saturn, art historians Margaret and Rudolf Wittkower’s excellent account of creativity’s more malign excesses, in a chapter titled “Suicides of Artists,” the authors quote from a 1738 notebook, written by a Ricci contemporary, “In the ardor of his youth Marco was a vicious fellow and given to a bad life; nor was he ashamed to mingle in taverns with vile plebians. One night in a tavern he felt offended by certain words of a gondoliere, whereupon he took a tankard, smashed it over the head of that unfortunate man and killed him.” Marco, the extravagantly talented capriccio painter, went on the lam.

Detail, Plate X, Varia/ Marci Ricci Pictores Praestantissimi /Experimenta, Marco Ricci, 1676 – 1730. Like Piranesi, Ricci lived in Venice, and was much influenced by the city’s artistic scene (before having to flee when he murdered a gondolier). The shimmering, uneven lines of his etchings, mirroring the reflected light characteristic of Venice, are easily seen in the slightly later etched works of Piranesi and Canaletto. Ricci’s influence extended as well to these artists’ choice of subject matter – the graphic work of all three pictures’ ancient ruins.

Years pass, Ricci’s artistic accomplishments accumulate, before “it suddenly came to his mind that he wanted to die, but to die like a knight. One morning, therefore, he dressed up most strangely, with a sword at his side, and lay down on his bed.” Death waited, though, until the artist forged his doctor’s prescription, in order to obtain a lethal dose of some unrecorded medicine.

Murderers, their intended victims, suicides – current offerings of etchings include high points from the oeuvre of each. Vasi’s vast view of Rome, richly provenanced to Chatsworth House, a pair of Ricci capricci, from his only series of etchings – Varia Marci Ricci Pictoris Prestantissimi Experimenta (fig. 3) – posthumously printed in 1720, the year of his death, and of course, and most variously and abundantly, Piranesi.

With Vasi’s very unruly pupil, we are thrilled to have available a half dozen rare etchings, from Invenzioni Caprice di Carceri, the c. 1750 first printing of what, ten years later, would be the very much re-worked (and celebrated) Carceri d’invenzione – Imaginary Prisons. Piranesi authority Arthur Hind wrote, just 100 years ago, in a May, 1911, number of Burlington Magazine – “The British Museum has recently acquired a rare and interesting series of early states of Piranesi’s Carceri. The existence of the early states had never been recognized until the discovery of this set, a short time ago …”

Among the abiding pleasures of these early etchings – some of Piranesi’s first graphic works – is their resolute lack of resolution. They appear rough sketches, drawings in progress; it is as though Piranesi had stepped away for a moment, perhaps to fetch a fresh etching needle or indulge an opium pipe, leaving us alone with his nascent, unfolding masterworks.

The later, much more familiar and heavily-inked, second edition of the Carceri, of which we’ve several appealing examples, evokes a different set of responses.

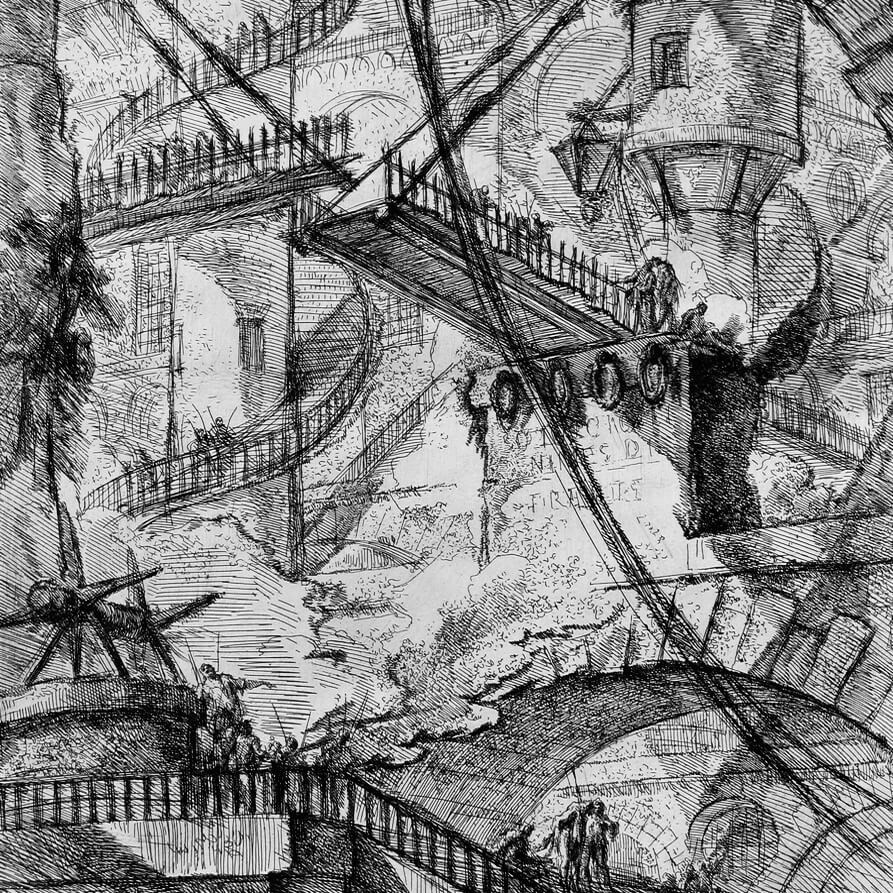

Figure 4. Detail: The Drawbridge (first state, c. 1750); Plate VII of Invenzioni Capric de Carceri, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

“Creeping along the sides of the walls, you perceive a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards was Piranesi himself… But raise your eyes and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived… Again elevate your eyes,… and again is poor Piranesi busy on his aspiring labors; and so on, until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom … Thomas de Quincy, Confessions of an Opium Eater, 1822

Thomas De Quincey, the British essayist, in his 1822 Confessions of an Opium Eater, describes the Carceri like an hallucination. “Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi’s Antiquities of Rome, Mr. Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist, and which record the scenery of his vision during the delirium of a fever.” (With Piranesi’s Prisons, this is a fever by which we’re fairly thrilled to be infected.) De Quincey continues –

Some of them (the Carceri) represented vast Gothic halls; on the floor of which stood all sorts of engines and machinery: wheels, cables, pulleys, levers, catapults, etc. etc., expressive of enormous power put forth and resistance overcome. Creeping along the sides of the walls, you perceive a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards was Piranesi himself; follow the stairs a little further and you perceive it comes to a sudden abrupt termination, without any balustrade, and allowing no step onwards to him who had reached the extremity, except into the depths below. Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi? You suppose, at least, that his labours must in some way terminate here. But raise your eyes and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived, by this time standing on the very brink of the abyss. Again elevate your eyes, and a still more aerial flight of stairs is beheld; and again is poor Piranesi busy on his aspiring labors; and so on, until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall. (fig. 4)

Our earlier discussion of 19th century Italian souvenir architectural models fashioned from stone touched briefly on mineralogy, the better to understand the remarkable truth that these slight mementos, almost always, are fashioned from ancient marbles and other decorative rock, brought to Rome millennia ago, from the furthest reaches of that then sprawling empire.

With the 18th and early 19th century architectural prints offered here, the medium’s historical sweep is less immense. Herr Gutenberg’s multiple printings of his 42-line Bible date only to 1455.

Figure 5. Veduta della Piazza di Monte Cavallo (1750), Giovanni Battista Piranesi, copper etching plate (above) with print (below). Among the etcher’s talents is the ability to imagine scenes in reverse. Owing to the printing process, Piranesi’s copper plate, including the scene and text, is designed to be “read” in mirror image, as seen in the complete print. Because copper is a soft metal, it is the early prints, taken before the copper wears, that are the sharpest. Some “Piranesi” etchings were printed into the 1930’s, and are predictably blotchy, indefinite images, dark shadows of their former selves.

And yet, as with the models, some technical understanding accelerates our appreciation of printed images. Despite the universe of printmaking techniques, we’ll focus on just two – etching and engraving – the predominant methods employed by Piranesi and his likeminded contemporaries.

Printmaking – including etchings, engravings, lithographs, aquatints, silkscreens, mezzotints, etc. – always involves the same process. A thin layer of ink is spread across a flat surface – a plate – onto which some meaningful shapes have first been incised. Once applied, the ink is then selectively removed; perhaps it remains in the plate’s crevices or along its ridges. Now “inked,” the plate is pressed hard against, most often, a sheet of paper, hard enough that the ink, adhering just so to the plate’s patterns of incisions, transfers just so, to the paper’s surface and thus is a print printed.

First, etching. With 18th century Italian architectural prints, the plates were very often of copper (fig. 5). Across this soft surface, was laid down a thin layer of varnish, sometimes, wax. Then the artist set to work, often with a sharp metal needle, “drawing” (actually inscribing) through the varnish, onto the copper plate below. Once the scene (of ruined temples and monuments, or more imaginary visions of the present day aftermaths of ancient civilization’s calamitous collapse) was laid in, the surface of the plate was washed with acid, which etched the metal exposed by the artist’s “drawing,” deepening the lines, leaving smooth the areas protected by varnish.

With removal of the varnish, the plate was ready for inking, and eventual printing of the finished image – an etching.

The process leading to an engraving sounds very similar. Instead of applying a masking layer of varnish, or employing acid to amplify a drawing’s lines, the artist takes up a variety of tools to cut – engrave – directly onto the surface of the plate. When this “drawing” is complete, the inking and printing process proceed, to complete the image – an engraving.

Despite their seemingly slight differences, opinions of the differences between etching and engraving have long been strongly held.

“According to the general opinion, and not without reason, etching is accounted more loose and painter-like than engraving, because there is no difference between etching and drawing, as to the execution; but the difference between drawing and engraving is very great. The management of the needle is almost the same with that of chalk or the pen: the plate lies flat and firm like the paper to draw upon. But we find the contrary in engraving; whereon the engraver is held almost parallel with the plate, and the latter is moveable on a cushion or seed-bag.”

A Treatise on the Art of Painting, in All its Branches (1817), Gerard de Lairesse

Figure 6. Detail, Portico with a Lantern, from Vedute (c. 1740), by Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto. Etching, unlike engraving, often consists of a fine, fluttering line, and is more approximate, more suggestion (more impressionistic) than the bolder, more certain lines often seen in engraving. In this detail from the painter Canaletto’s imaginary capriccio view of Venetian ruins, surfaces appear almost in motion, roiled by the city’s distinctive daylight, rich in many of those ways seen in the artist’s much more familiar paintings.

Alongside this rhapsodizing, though, alongside the elegant distinction between etching and engraving are some disruptive truths, exampled, by Cavalier Piranesi. More recently, art historians have made much of etching’s painterly line – seen in the Venetian prints of Ricci and Piranesi, and those of hometown artists Tiepolo and Canaletto (fig. 6). This fluttering, shimmering, irregular line gives form to the city’s distinctive light – refracted across the liquid surface of canals and lagoons; reflected in ultramarine skies and reflected across richly hued and textured plaster walls. Especially with his Carceri, Piranesi employed not simply etching, but also engraving (and a host of other techniques).

“…he used both burin and etching needle to scape and scratch lines of every depth and width, while the burnisher was used to soften lines and create lighter patches. He created areas of gray throughout the plate by means of shallow surface scratches that held a light film of ink. In other places he applied acid directly to the plate in order to roughen it, resulting in scattered black spots. The brightest highlight of (these prints) has been achieved by adding a resistant ground to an isolated spot before inking the plate – the ground covers any etched lines in that area, as well as accidental scratches, so that the area prints a pure white in the midst of a wide range of blacks and grays.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

If the tidy distinctions of printmaking give way before the onrushing force of Piranesi’s vision, this cannot be counted a loss. With remarkable possibilities at hand, why be bound by methodological purities? For Piranesi (the artist was knighted in 1766, by Pope Clement Xii, and henceforth called himself Cavalier), as for Malcolm X, the imperative is to “bring about the freedom by any means necessary.”